3D printing technique allows polymers to be added retrospectively

By depositing layer upon layer of polymers in a precisely determined pattern, three-dimensional printing technology makes it possible to rapidly manufacture objects. Once these objects are completed, the polymers that form the material are ‘dead’ — that is, they cannot be extended to form new polymer chains.

MIT chemists have now developed a technique that allows them to print objects and then go back and add new polymers that alter the materials’ chemical composition and mechanical properties. The researchers can also fuse two or more printed objects together to form more complex structures.

“The idea is that you could print a material and subsequently take that material and, using light, morph the material into something else, or grow the material further,” says Jeremiah Johnson, the Firmenich Career Development Associate Professor of Chemistry at MIT.

This technique could greatly expand the complexity of objects that can be created with 3D printing, says Johnson, the senior author of a paper describing the approach in the Jan. 13 issue of ACS Central Science. The paper’s lead authors are former MIT postdoc Mao Chen and graduate student Yuwei Gu.

Living polymerization

One of the most common techniques used for 3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, is stereolithography. By shining light onto a liquid solution of monomers, the building blocks of plastic and other materials, stereolithography devices can form layers of solid polymers until the final shape is completed.

Several years ago, Johnson and his colleagues set out to create adaptable 3D-printed structures by taking advantage of a technique known as “living polymerization,” which yields materials whose growth can be halted and then restarted later on.

In 2013, the researchers demonstrated that they could use a type of polymerization stimulated by ultraviolet light to add new features to 3D-printed materials. After printing an object, the researchers used ultraviolet light to break apart the polymers at certain points, creating very reactive molecules called free radicals. These radicals would then bind to new monomers from a solution surrounding the object, incorporating them into the original material.

“The advantage there is you can turn the light on and the chains grow, and you turn the light off and they stop,” Johnson says. “In principle, you can repeat that indefinitely and they can continue growing and growing.”

However, this approach proved to be too damaging to the material and difficult to control, because free radicals are so reactive.

New properties

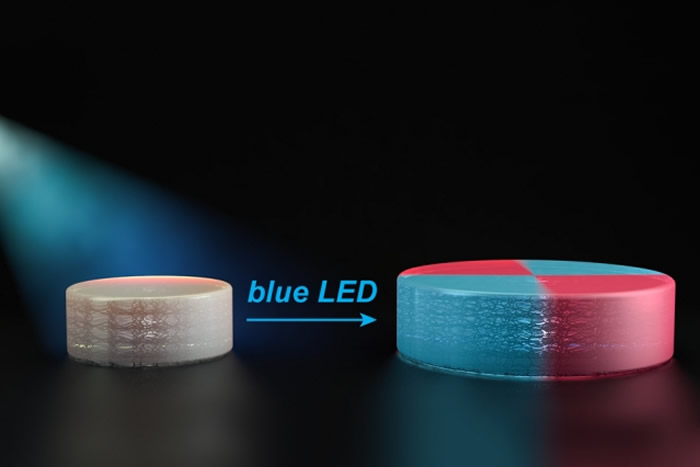

In their next effort, the researchers designed new polymers that are also reactivated by light, but in a slightly different way. Each of the polymers contains chemical groups that act like a folded up accordion. These chemical groups, known as TTCs, can be activated by organic catalysts that are turned on by light. When blue light from an LED shines on the catalyst, it attaches new monomers to the TTCs, making them stretch out. As these monomers are incorporated uniformly throughout the structure, they give the material new properties.

“That’s the breakthrough in this paper: We really have a truly living method where we can take macroscopic materials and grow them in the way we want to,” Johnson says.

In the ACS Central Science paper, the researchers demonstrated that they can incorporate monomers that alter a material’s mechanical properties, such as stiffness, and its chemical properties, including hydrophobicity (affinity for water). They also showed that they could make materials swell and contract in response to temperature by adding a certain type of monomer.

The researchers also used this approach to fuse two structures together, by shining light on the regions where they come in contact with each other.

Cyrille Boyer, an associate professor of chemical engineering at the University of New South Wales, who was not involved in the research, described the study as “an inspiring paper for the generation of ‘living’ gels capable to grow and duplicate using visible light and photoredox catalysts. By merging two fields, polymer science and materials science, Johnson and co-workers designed new thermal responsive gels and have overcome the current limitations in the preparation of gels.”

One limitation of this technique is that the organic catalyst requires an oxygen-free environment. The researchers are now testing some other catalysts that have been reported to catalyze similar polymerizations but can be used in the presence of oxygen.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation.

More information: Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.