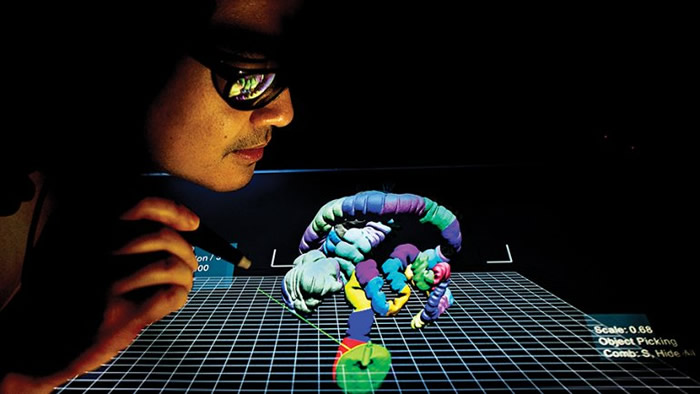

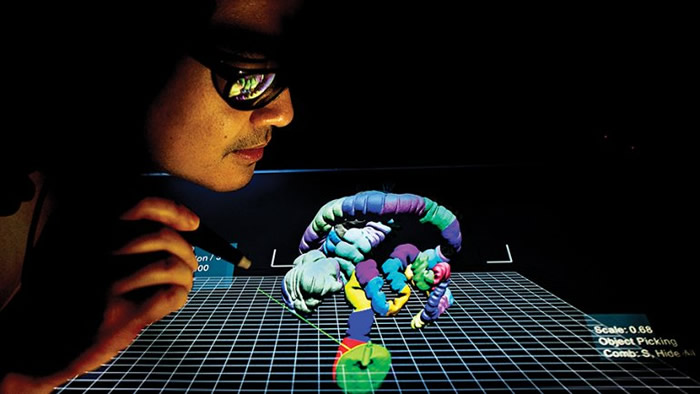

Radiologist Judy Yee, MD, at UCSF’s 3D Imaging Lab pulls up an image that looks more like a birthday party balloon animal than a patient’s colon: a vibrant, color-segmented tube, torqued and twisted in on itself. Created from thin slices of a CT scan, the image appears in 3D on the flat screen. It can even morph into video “fly-through” views, enhancing polyps, lesions, and other precancerous anomalies.

Yee refined this revolutionary blend of advanced graphical software and scanning technology – known as CT colonography (CTC) or virtual colonoscopy – as a far less invasive and easier-to-interpret alternative to conventional colonoscopies.

Yee, professor and vice chair of the Department of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging at UCSF and ch

ief of radiology at San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, is now pushing radiology even further with holograms.

Virtual holography CTC is the latest phase in her two decades of research committed to earlier, safer, life-saving detection of colorectal cancer. Though the disease is often preventable, it is the second most common cause of cancer deaths in the United States.

“When screening for breast cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer and other malignancies, we’re typically looking for the cancer itself. By then it’s too late,” Yee says. “Here we have a specific pathology that allows us to find a lesion (known as a polyp) before it turns into cancer. If we could just get more patients to come in for screening, we could certainly have a huge impact on preventing colorectal cancer.”

Yee slips on a pair of 3D black metal-rimmed glasses and points a laser stylus at the monitor still displaying her patient’s colon. By flicking the stylus and turning her head while keeping her eyes on the monitor, Yee is suddenly “inside” the colon, moving through it, pulling it toward her, spinning it around.

Using 3D technology, UCSF doctors can isolate and examine parts of the bowel in detail without using invasive cameras.

As she moves, a computer monitor with stereoscopic optical technology tracks her glasses, which have different polarisation in each lens, prompting her brain to construct a virtual holographic object that recreates the size and shape of the human anatomy.

The stylus, working in tandem with advanced graphical processing of the CTC image, allows her to “grab” the portion of the scan she wants to examine in more detail and interact with it in three-dimensional space.

“I don’t know of anyone else who is doing this,” Yee says, about UCSF’s blending of radiology with virtual holography. “You can cut away the parts of what you don’t want to see and manipulate it so that you improve what you do want to see. It’s a more engaging way to read large data sets.

With the added dimension, you can see flat, more dangerous lesions better.” The technology also has far-reaching promise for neurological, cardiac, and musculoskeletal applications, she adds. ”

As the equipment evolves, it allows us to view the same disease processes in a completely different way so we can improve detection and diagnostic ability and streamline workflow,” Yee says. “This could go a long way toward helping show what radiology can bring to patient diagnosis and management for all different parts of the body.”

More information: University of California, San Francisco

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.