Supercapacitor uses no conductive carbon

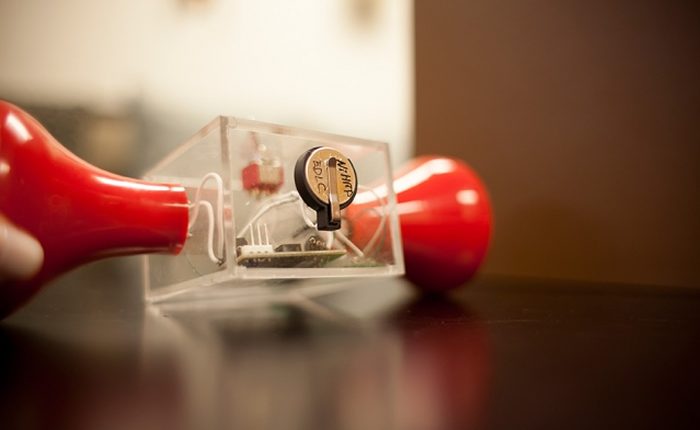

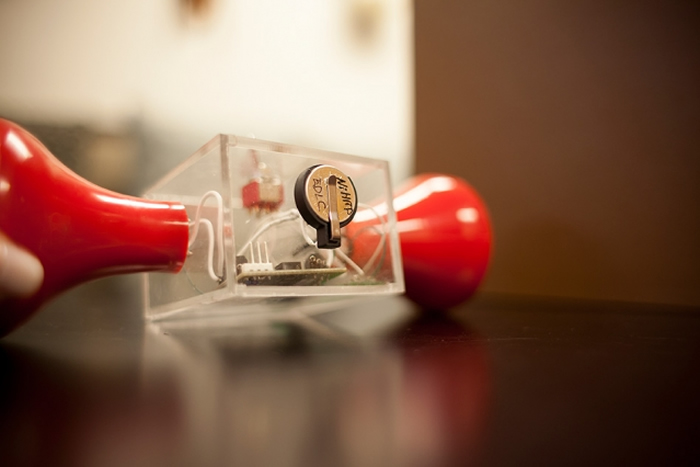

Energy storage devices called supercapacitors have become a hot area of research, in part because they can be charged rapidly and deliver intense bursts of power. However, all supercapacitors currently use components made of carbon, which require high temperatures and harsh chemicals to produce.

Now researchers at MIT and elsewhere have for the first time developed a supercapacitor that uses no conductive carbon at all, and that could potentially produce more power than existing versions of this technology.

The team’s findings are being reported in the journal Nature Materials, in a paper by Mircea Dincă, an MIT associate professor of chemistry; Yang Shao-Horn, the W.M. Keck Professor of Energy; and four others.

“We’ve found an entirely new class of materials for supercapacitors,” Dincă says. Dincă and his team have been exploring for years a class of materials called metal-organic frameworks, or MOFs, which are extremely porous, sponge-like structures. These materials have an extraordinarily large surface area for their size, much greater than the carbon materials do. That is an essential characteristic for supercapacitors, whose performance depends on their surface area. But MOFs have a major drawback for such applications: They are not very electrically conductive, which is also an essential property for a material used in a capacitor.

“One of our long-term goals was to make these materials electrically conductive,” Dincă says, even though doing so “was thought to be extremely difficult, if not impossible.” But the material did exhibit another needed characteristic for such electrodes, which is that it conducts ions (atoms or molecules that carry a net electric charge) very well.

“All double-layer supercapacitors today are made from carbon,” Dincă says. “They use carbon nanotubes, graphene, activated carbon, all shapes and forms, but nothing else besides carbon. So this is the first noncarbon, electrical double-layer supercapacitor.”

One advantage of the material used in these experiments, technically known as Ni3(hexaiminotriphenylene)2, is that it can be made under much less harsh conditions than those needed for the carbon-based materials, which require very high temperatures above 800 degrees Celsius and strong reagent chemicals for pretreatment.

The team says supercapacitors, with their ability to store relatively large amounts of power, could play an important role in making renewable energy sources practical for widespread deployment. They could provide grid-scale storage that could help match usage times with generation times, for example, or be used in electric vehicles and other applications.

The new devices produced by the team, even without any optimization of their characteristics, already match or exceed the performance of existing carbon-based versions in key parameters, such as their ability to withstand large numbers of charge/discharge cycles. Tests showed they lost less than 10 percent of their performance after 10,000 cycles, which is comparable to existing commercial supercapacitors.

But that’s likely just the beginning, Dincă says. MOFs are a large class of materials whose characteristics can be tuned to a great extent by varying their chemical structure. Work on optimizing their molecular configurations to provide the most desirable attributes for this specific application is likely to lead to variations that could outperform any existing materials. “We have a new material to work with, and we haven’t optimized it at all,” he says. “It’s completely tunable, and that’s what’s exciting.”

While there has been much research on MOFs, most of it has been directed at uses that take advantage of the materials’ record porosity, such as for storage of gases. “Our lab’s discovery of highly electrically conductive MOFs opened up a whole new category of applications,” Dincă says. Besides the new supercapacitor uses, the conductive MOFs could be useful for making electrochromic windows, which can be darkened with the flip of a switch, and chemoresistive sensors, which could be useful for detecting trace amounts of chemicals for medical or security applications.

While the MOF material has advantages in the simplicity and potentially low cost of manufacturing, the materials used to make it are more expensive than conventional carbon-based materials, Dincă says. “Carbon is dirt cheap. It’s hard to find anything cheaper.” But even if the material ends up being more expensive, if its performance is significantly better than that of carbon-based materials, it could find useful applications, he says.

This discovery is “very significant, from both a scientific and applications point of view,” says Alexandru Vlad, a professor of chemistry at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium, who was not involved in this research. He adds that “the supercapacitor field was (but will not be anymore) dominated by activated carbons,” because of their very high surface area and conductivity. But now, “here is the breakthrough provided by Dinca et al.: They could design a MOF with high surface area and high electrical conductivity, and thus completely challenge the supercapacitor value chain! There is essentially no more need of carbons for this highly demanded technology.”

And a key advantage of that, he explains, is that “this work shows only the tip of the iceberg. With carbons we know pretty much everything, and the developments over the past years were modest and slow. But the MOF used by Dinca is one of the lowest-surface-area MOFs known, and some of these materials can reach up to three times more [surface area] than carbons. The capacity would then be astonishingly high, probably close to that of batteries, but with the power performance [the ability to deliver high power output] of supercapacitors.”

The research team included former MIT postdoc Dennis Sheberla (now a postdoc at Harvard University), MIT graduate student John Bachman, Joseph Elias PhD ’16, and Cheng-Jun Sun of Argonne National Laboratory. The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy through the Center for Excitonics, the Sloan Foundation, the Research Corporation for Science Advancement, 3M, and the National Science Foundation.

More information: Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.