Recent research has explored the possibility of all-solid-state batteries, in which the liquid (and potentially flammable) electrolyte would be replaced by a solid electrolyte, which could enhance the batteries’ energy density and safety.

Now, for the first time, a team at MIT has probed the mechanical properties of a sulfide-based solid electrolyte material, to determine its mechanical performance when incorporated into batteries.

The new findings were published this week in the journal Advanced Energy Materials, in a paper by Frank McGrogan and Tushar Swamy, both MIT graduate students; Krystyn Van Vliet, the Michael (1949) and Sonja Koerner Professor of Materials Science and Engineering; Yet-Ming Chiang, a professor of materials science and engineering; and four others including an undergraduate participant in the National Science Foundation Research Experience for Undergraduate (REU) program administered by MIT’s Center for Materials Science and Engineering and its Materials Processing Center.

Lithium-ion batteries have provided a lightweight energy-storage solution that has enabled many of today’s high-tech devices, from smartphones to electric cars. But substituting the conventional liquid electrolyte with a solid electrolyte in such batteries could have significant advantages. Such all-solid-state lithium-ion batteries could provide even greater energy storage ability, pound for pound, at the battery pack level. They may also virtually eliminate the risk of tiny, fingerlike metallic projections called dendrites that can grow through the electrolyte layer and lead to short-circuits.

“Batteries with components that are all solid are attractive options for performance and safety, but several challenges remain,” Van Vliet says. In the lithium-ion batteries that dominate the market today, lithium ions pass through a liquid electrolyte to get from one electrode to the other while the battery is being charged, and then flow through in the opposite direction as it is being used. These batteries are very efficient, but “the liquid electrolytes tend to be chemically unstable, and can even be flammable,” she says. “So if the electrolyte was solid, it could be safer, as well as smaller and lighter.”

But the big question regarding the use of such all-solid batteries is what kinds of mechanical stresses might occur within the electrolyte material as the electrodes charge and discharge repeatedly. This cycling causes the electrodes to swell and contract as the lithium ions pass in and out of their crystal structure. In a stiff electrolyte, those dimensional changes can lead to high stresses. If the electrolyte is also brittle, that constant changing of dimensions can lead to cracks that rapidly degrade battery performance, and could even provide channels for damaging dendrites to form, as they do in liquid-electrolyte batteries. But if the material is resistant to fracture, those stresses could be accommodated without rapid cracking.

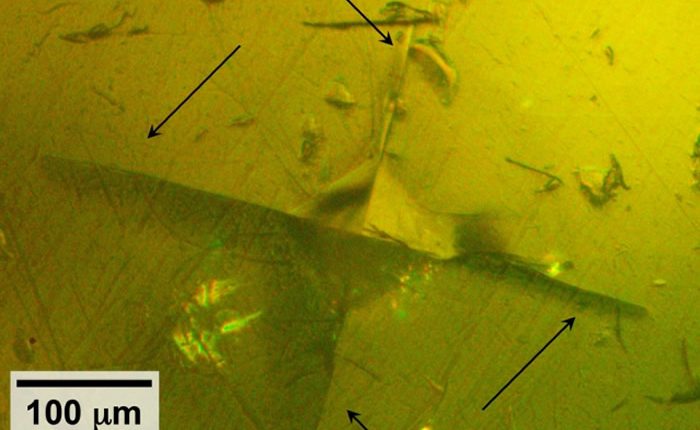

Until now, though, the sulfide’s extreme sensitivity to normal lab air has posed a challenge to measuring mechanical properties including its fracture toughness. To circumvent this problem, members of the research team conducted the mechanical testing in a bath of mineral oil, protecting the sample from any chemical interactions with air or moisture. Using that technique, they were able to obtain detailed measurements of the mechanical properties of the lithium-conducting sulfide, which is considered a promising candidate for electrolytes in all-solid-state batteries.

“There are a lot of different candidates for solid electrolytes out there,” McGrogan says. Other groups have studied the mechanical properties of lithium-ion conducting oxides, but there had been little work so far on sulfides, even though those are especially promising because of their ability to conduct lithium ions easily and quickly.

Previous researchers used acoustic measurement techniques, passing sound waves through the material to probe its mechanical behavior, but that method does not quantify the resistance to fracture. But the new study, which used a fine-tipped probe to poke into the material and monitor its responses, gives a more complete picture of the important properties, including hardness, fracture toughness, and Young’s modulus (a measure of a material’s capacity to stretch reversibly under an applied stress).

“Research groups have measured the elastic properties of the sulfide-based solid electrolytes, but not fracture properties,” Van Vliet says. The latter are crucial for predicting whether the material might crack or shatter when used in a battery application.

The researchers found that the material has a combination of properties somewhat similar to silly putty or salt water taffy: When subjected to stress, it can deform easily, but at sufficiently high stress it can crack like a brittle piece of glass.

By knowing those properties in detail, “you can calculate how much stress the material can tolerate before it fractures,” and design battery systems with that information in mind, Van Vliet says.

The material turns out to be more brittle than would be ideal for battery use, but as long as its properties are known and systems designed accordingly, it could still have potential for such uses, McGrogan says. “You have to design around that knowledge.”

“The cycle life of state-of-the-art Li-ion batteries is primarily limited by the chemical/electrochemical stability of the liquid electrolyte and how it interacts with the electrodes,” says Jeff Sakamoto, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Michigan, who was not involved in this work. “However, in solid-state batteries, mechanical degradation will likely govern stability or durability. Thus, understanding the mechanical properties of solid-state electrolytes is very important,” he says.

Sakamoto adds that “Lithium metal anodes exhibit a significant increase in capacity compared to state-of-the-art graphite anodes. This could translate into about a 100 percent increase in energy density compared to [conventional] Li-ion technology.”

The research team also included MIT researchers Sean Bishop, Erica Eggleton, Lukas Porz, and Xinwei Chen. The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Basic Energy Science for Chemomechanics of Far-From-Equilibrium Interfaces.

More information: Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)