Next-generation Data Storage Possible When Skyrmion State Maintained at Room Temperature

Over the next decade, streaming data, the Internet of Things, video, artificial intelligence and machine learning (ML) are driving our need for data storage into the exabyte range. As demand for data storage and processing have grown exponentially while the world becomes increasingly connected, we need new materials capable of more efficient data storage and data processing.

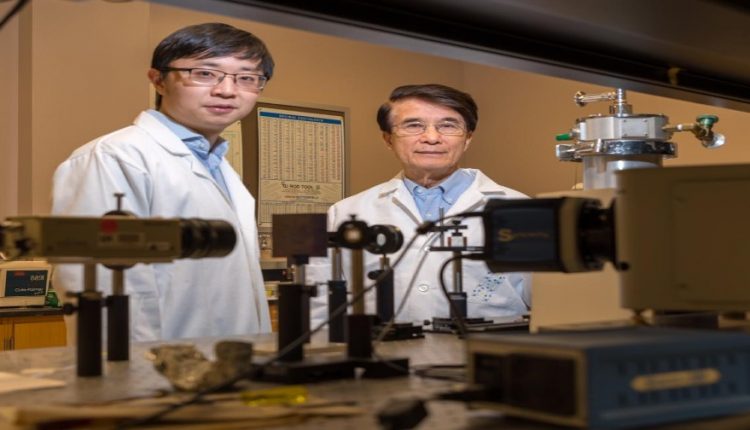

Now an international team of researchers, led by physicist Paul Ching-Wu Chu, founding director of the Texas Center for Superconductivity at the University of Houston, is reporting a new compound capable of maintaining its skyrmion properties at room temperature through the use of high pressure. The results also suggest the potential for using chemical pressure to maintain the properties at ambient pressure, offering promise for commercial applications.

The work is described in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

A skyrmion is the smallest possible perturbation to a uniform magnet, a point-like region of reversed magnetization surrounded by a whirling twist of spins. These extremely small regions, along with the possibility of moving them using very little electrical current, make the materials hosting them promising candidates for high-density information storage. But the skyrmion state normally exists only at a very low and narrow temperature range. For example, in the compound Chu and colleagues studied, the skyrmion state normally exists only within a narrow temperature range of about 3 Kelvin degrees, between 55 K and 58.5 K (between -360.7 Fahrenheit and -354.4 Fahrenheit). That makes it impractical for most applications.

Working with a copper oxyselenide compound, Chu said the researchers were able to dramatically expand the temperature range at which the skyrmion state exists, up to to 300 degrees Kelvin, or about 80 degrees Fahrenheit, near room temperature. First author Liangzi Deng said they successfully detected the state at room temperature for the first time under 8 gigapascals, or GPa, of pressure, using a special technique he and colleagues developed. Deng is a researcher with the Texas Center for Superconductivity at UH (TcSUH).

Chu, the corresponding author for the work, said researchers also found that the copper oxyselenide compound undergoes different structural-phase transitions with increasing pressure, suggesting the possibility that the skyrmion state is more ubiquitous than previously thought.

“Our results suggest the insensitivity of the skyrmions to the underlying crystal lattices. More skyrmion material may be found in other compounds, as well,” Chu said.

The work suggests the pressure required to maintain the skyrmion state in the copper oxyselenide compound could be replicated chemically, allowing it to work under ambient pressure, another important requirement for potential commercial applications. That has some analogies to work Chu and his colleagues did with high-temperature superconductivity, announcing in 1987 that they had stabilized high-temperature superconductivity in YBCO (yttrium, barium, copper, and oxygen) by replacing ions in the compound with smaller isovalent ions.

Source: University of Houston