Researchers implant device in mouse’s brain to wirelessly control its behavior

The field of optogenetics uses light to control the brain’s activity. Typically researchers have attached a fiber optic cable to a mouse’s head in order to deliver light and control the nerves.

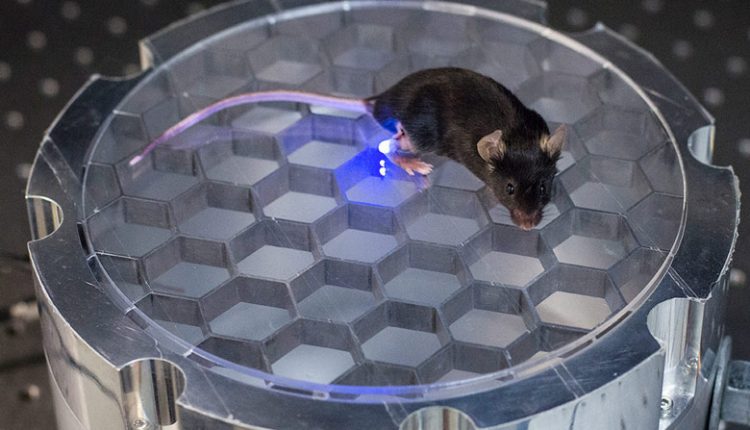

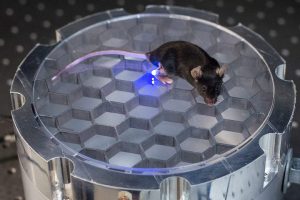

Now, researchers from Stanford University’s Bio-X team have figured out a way to control the brain wirelessly by placing a blue glowing device inside of a mouse brain and delivering optogenetic nerve stimulation in an implantable way.

In the team’s research, the energy being transmitted to the device is actually powered by the mouse’s own body and delivers light to stimulate the nerves of its legs.

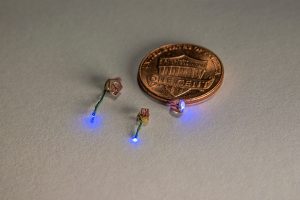

“This is a new way of delivering wireless power for optogenetics,” said Ada Poon, an assistant professor of electrical engineering at Stanford, in a news release. “It’s much smaller and the mouse can move around during an experiment.”

Prior to this new method, mice were forced to wear restrictive headgear and scientists had to handle the mice often, which could have altered test results and provided restrictions on the knowledge they were able to acquire.

Prior to this research, Poon developed implantable wirelessly powered devices. So it’s no surprise that her knowledge would be transferred to the field of optogenetics, opening the door to learn more about issues like depression and anxiety.

In order for optogenetics to work, the researchers must prepare the nerves in the subject’s body so that they contain the proteins that respond to light — either by breeding mice that contain these proteins or injecting them into the nerves. So this device couldn’t be implanted in just anyone.

One challenge that Poon and the team faced was determining how to power the device without compromising power efficiency.

For example, during testing, the mouse would move all around, and “the researchers needed a way of tracking that movement to provide localized power,” according to the news release.

Instead, Poon opted to use the mouse’s own body for power by transferring radio frequency energy of just the right wavelength into the mouse. They equipped each mouse with a chamber, and wherever the mouse moved, its body would come in contact with energy, drawing it in and powering its implanted device. Any extra energy would be stored in its chamber.

“The device is small enough to be implanted under the skin and may even be able to trigger a signal in muscles or some organs, which were previously not accessible to optogenetics,” according to Stanford.

The team hopes that the new method and device will open the door to a better understanding of mental health disorders, movements disorders, and internal organ diseases. They will also begin developing new treatments for chronic pain.

Story via Stanford University.