Leaping lizards? Nope, squirrels

Inspiration comes from many sources. In this case, U.S. Army, researchers at University of California, Berkeley studied how squirrels decide whether or not to take a leap and how they assess their biomechanical abilities to know whether they can land safely. Their split-second decision may help scientists develop agile robots.

The goal of the study is to help scientists design autonomous robots that nimbly move through varied landscapes for military missions such as traveling through the rubble of a collapsed building, to aid in search and rescue, or to quickly access an environmental threat.

The research team developed precise methods to study cognition in wild campus squirrels, and proposed integrating these studies with biomechanics, extending laboratory models not only to mammals for the first time, but to a wild mammal–squirrels–that had experienced the full natural agility development.

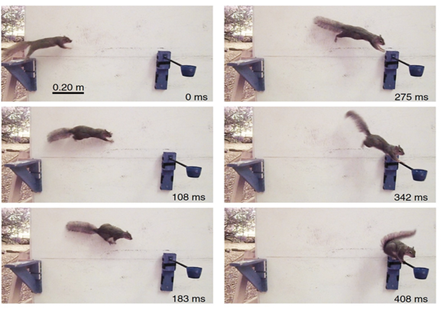

In the journal Science, the researchers report on their experiments on free-ranging squirrels, quantifying how they learn to leap from different types of launching pads. They found that the flimsier or more compliant the branch from which squirrels have to leap, the more cautious they were. But, it took squirrels just a few attempts to adjust to different compliances. Squirrels don’t balance the bendiness of the launching branch and the gap distance equally. In fact, the compliance of the branch was six times more critical than the gap distance in deciding whether to jump. An unsuspected innovation was that during tricky jumps, squirrels would often reorient their bodies to push off a vertical surface, like in human parkour, to adjust their speed and insure a better landing. Parkour is a sport in which people leap, vault, swing to quickly traverse obstacles without the use of equipment.

The study will help engineers understand how to design a robot controller and actuators to maximize improvisational capabilities.

Original Release: Eureka Alert