Researchers at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) are too cool for school… and too hot.

They’ve created a building material that changes its infrared color based on the amount of heat it absorbs or emits based on daily temperatures. On hot days it can emit up to 92% of its heat, helping to cool the inside of the building, whereas, on cold days, it reduces its heat emission to help keep the building warm.

“We’ve essentially figured out a low-energy way to treat a building like a person,” said Asst. Prof. Po-Chun Hsu, who led the research published in Nature Sustainability, “you add a layer when you’re cold and take off a layer when you’re hot. This kind of smart material lets us maintain the temperature in a building without huge amounts of energy.”

Some estimates say that buildings account for about 30% of global energy consumption and emit 10% of global greenhouse gas. Nearly half of this energy footprint is due to our heating and cooling systems. Many of us take our thermostats for granted. While smart home systems can help us save energy, Hsu says, “If we want a carbon-negative future, I think we have to consider diverse ways to control building temperature in a more energy-efficient way.”

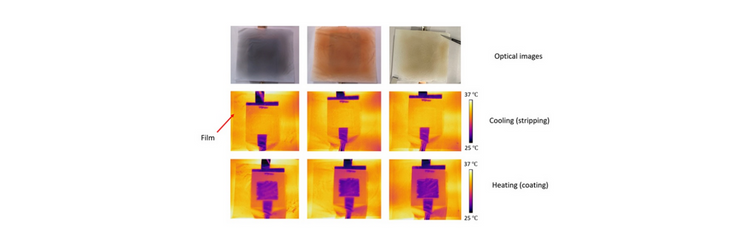

The new material is a non-flammable “electrochromic” material with a layer that changes states based on the temperature. When it is solid copper, it retains most of its infrared heat, but by emitting a tiny electrical pulse, the copper layer liquifies, becoming a watery solution that emits infrared. In the new paper, the researchers detailed how the device can switch rapidly and reversibly between the metal and liquid states. They showed that switching between the two conformations remained efficient even after 1,800 cycles.

The team also created models showing how their material could cut energy costs in typical buildings in 15 different U.S. cities. An average commercial building could save 8.4% of its annual HVAC energy use while only needing less than 0.2% of its total electricity consumption to switch the material’s state.

So far, the group has only created pieces measuring six centimeters across; however, they believe engineers could assemble their material like shingles into larger pieces.

What I want to know? When can I put it on my house?