Now researchers can 3D-print lab instruments like Lego blocks

Now when universities, schools, and hospitals need a scientific tool, they’ll be able to custom 3D print them in block form quickly and inexpensively.

A team from the University of California, Riverside has created the Lego-like system of blocks, which allows users to custom-build chemical and biological research instruments whenever they want.

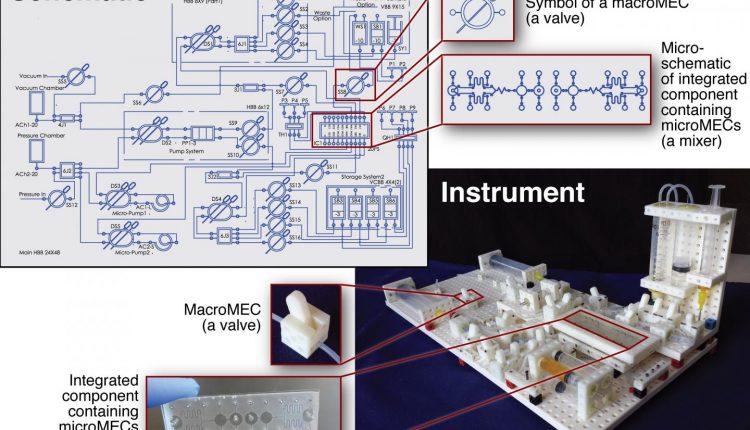

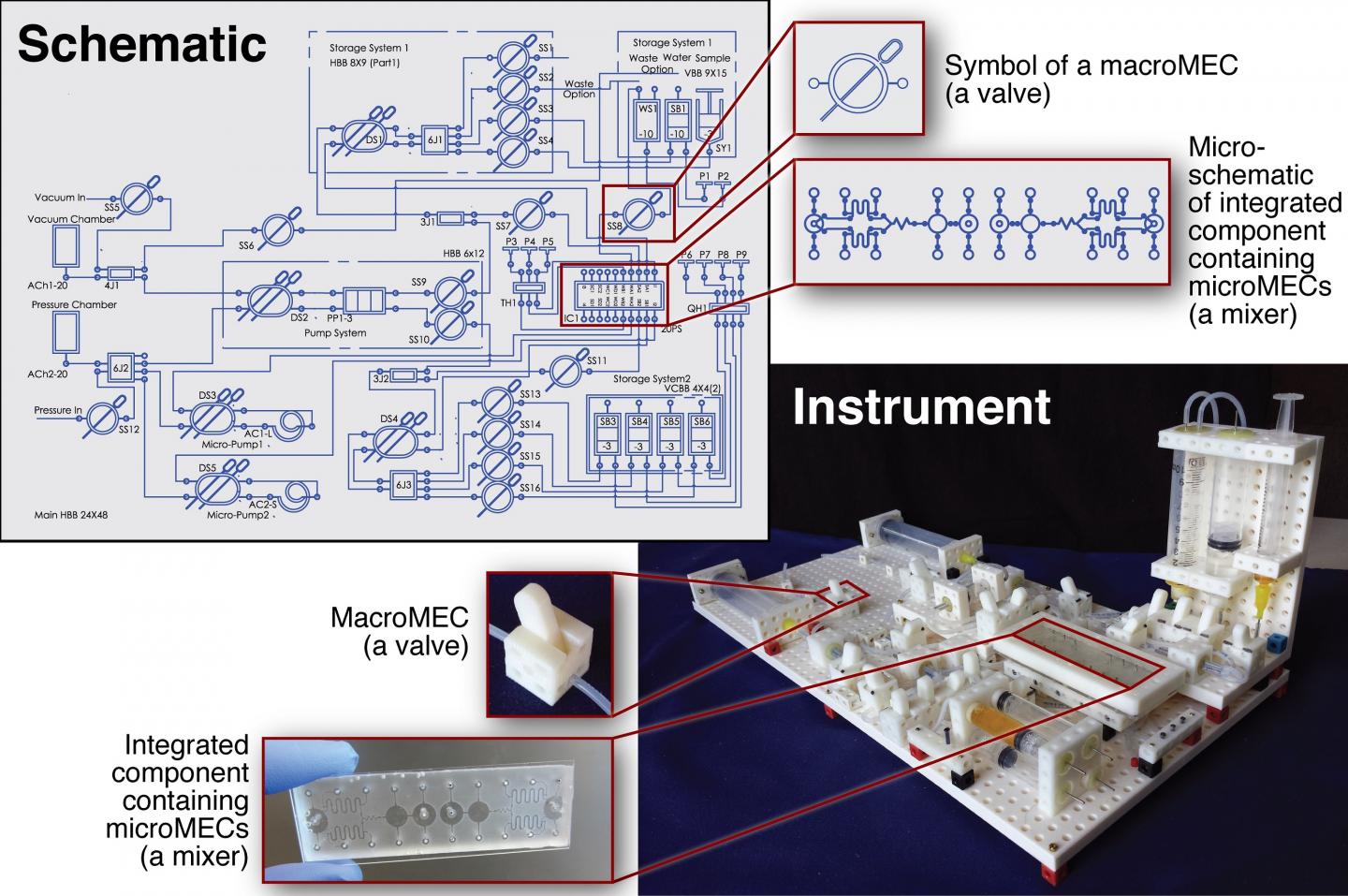

The blocks, called Multifluidic Evolutionary Components (MECs) due to their flexibility and adaptability, each perform a basic task found in a lab instrument —for example, pumping fluids, making measurements or interfacing with a user. Since the blocks are designed to work together, users can build apparatus like bioreactors for making alternative fuels or acid-base titration tools for high school chemistry classes pretty quickly.

The blocks would be most useful in areas where resources are limited, allowing for a library of blocks to be used to create a variety of different research and diagnostic tools.

The project was sparked by Douglas Hill, a graduate student who worked for 20 years in the field of electronics design, where he used electronic components that were designed to work with each other. He was surprised when he got the UC Riverside to find that there was no similar set of components in the life sciences.

“When Doug came to UC Riverside, he was a little shocked to find out that bioengineers build new instruments from scratch,” said William Grover, assistant professor of bioengineering in UCR’s Bourns College of Engineering. “He’s used to putting together a few resistors and capacitors and making a new circuit in just a few minutes. But building new tools for life science research can take months or even years. Doug set out to change that.”

Hill and Grover began to develop their building blocks with help from a team of UC Riverside undergraduates who designed new blocks and built instruments using the blocks. Since the development, more than 50 other students have participated and created an extensive system of over 200 blocks and a system of schematics that guide assembly into finished instruments.

“This is a truly interdisciplinary project–we’ve had computer science students write the code that runs the blocks, bioengineering students culture cells using instruments built from the blocks, and even art students design the graphical interface for the software that controls the blocks,” said Grover. “Once the students have created these instruments, they also understand how they work, they can ‘hack’ them to make them better, and they can take them apart to create something else.”

The duo are now planning to pilot the system in two California school districts, where it will work in conjunction with a new initiative to strengthen science education in K-12 schools.

“The Next Generation Science Standards require that science teachers provide their students with engineering experiences, but sometimes that’s hard for teachers to do, especially in biology and chemistry classes where they might not have the tools they need. By using our blocks, the students can receive an engineering experience by designing, building, and refining their instruments, and also a science experience as they use their instruments to learn about biology and chemistry,” said Grover.

According to Hill, the team’s long-term goal is to make the blocks available and affordable for others to use.

“As 3D printers become more mainstream, we’ll see them being used by schools and non-profits working in underserved communities, so ultimately we would like people to be able to use those printers to create their own MEC blocks and build the research and educational tools they need,” said Hill.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.