A hybrid network using satellite airwaves

A company named LightSquared proposed something no wireless carrier had done before: It vowed to build America’s first retail cellphone network using airwaves traditionally reserved for orbiting satellites.

The idea was exciting — and unproven. While mainstream carriers such as Verizon and AT&T waged war over more traditional low-frequency airwaves, Reston-based LightSquared wanted to beam mobile Internet from cell towers to customer smartphones over high-frequency waves, bypassing the competition and entering as a new, hungry rival in a market dominated by big corporations. It was seizing on the potential of what was, at the time, less desirable airwaves.

But the project quickly fell behind. With a $3bn investment at stake, LightSquared filed for bankruptcy protection in 2012 after failing to keep up with its debts and becoming embroiled in a high-stakes confrontation with John Deere, Garmin and even the military. The once-radical effort stalled.

After a multiyear restructuring during which LightSquared’s owner and top investor — the embattled hedge-fund manager Philip Falcone — stepped aside, the company has reemerged. It has a new name — Ligado — and even grander ambitions.

If it succeeds, Ligado will be well-positioned to control a massive chunk of the industrial market for connected devices, a market that Morgan Stanley thinks will be worth $110bn a year by 2020. Success, however, depends on billions of dollars of investment in construction, not to mention getting the blessing of regulators who blocked the company’s path once before.

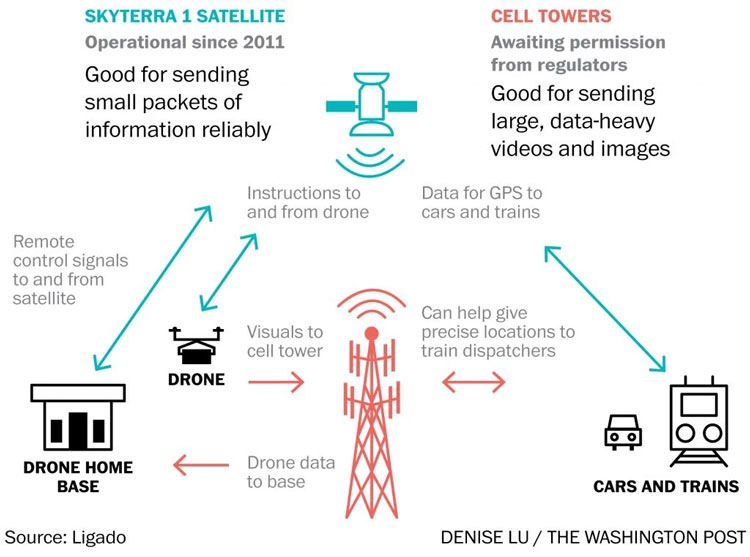

Ligado is promising not only to build the world’s first wireless network using ground-based airwaves that had long been considered unsuitable for cellular use, but it’s also planning to join that capability with a satellite hovering above North America. The novel pairing, its executives say, will largely support industrial customers, not individual consumers. But, they emphasize, that doesn’t mean the average American won’t see benefits from the hybrid network.

“It’s new owners, a new board, a new management team,” Ligado Chief Executive Doug Smith said. “We’re excited with the solution we came up with. This is not another cellphone network. It is absolutely a type of service that doesn’t exist today.”

For example, the new system could allow self-driving cars to receive instant GPS location readings that are accurate to within five inches, according to Smith. Achieving that level of accuracy will probably become vital to the automotive industry as vehicle automation goes mainstream — whether for parallel parking or for staying in the correct lane at 60mph.

Ligado’s satellite-terrestrial network could also give railroad companies a boost. The high-precision location features may allow train dispatchers to pinpoint the precise endpoints of a train, which could help avoid collisions or improve the efficiency of rail operations.

“Knowing exactly where that end-of-train is at any moment makes it much safer,” said Sid Bakker, President of TPSC, a railroad telecommunications provider. “If we can communicate that to the back office, or to other trains or maintenance vehicles, we just increase driver safety.”

Emergency helicopter services could benefit from satellite-terrestrial communications, too — enabling rescue workers to keep their choppers humming at peak performance by automatically sending diagnostic data back to base. That data about the equipment could help maintenance crews anticipate a mechanical or electronic problem in the aircraft before it begins.

In an industry in which everything is fine-tuned to the last detail and backed up by contingency plans, the inability to get live, real-time maintenance data from aircraft is the missing piece, said Mike Stanberry, chief executive of Shreveport, La.-based Metro Aviation, which supplies helicopters and maintenance services to hospitals across the country.

“We were killing people in the industry because we were deficient in these areas,” Stanberry said. “This live data information was the last bucket, and probably the most important.”

Ligado’s network will be built in stages. Although the company’s main satellite, SkyTerra 1, has been operational since 2011, Ligado is awaiting permission from federal regulators to begin building ground-based cell towers. The first beneficiaries will be such companies as TPSC and Metro Aviation, along with ports, utility companies and other industrial businesses. Because most of these firms operate in geographically specific areas, don’t expect Ligado to build a national cellular footprint anytime soon. It’ll start by setting up ground-based towers in just the places that need them most, said its Executive Vice President, Valerie Green.

The network is expected to split its duties according to the type of traffic it’s handling. For relatively small packets of information that require high speed and low drag — such as diagnostic data — the satellite connection will be key. But the ground-based network will handle more bandwidth-heavy applications, such as the video produced by an aerial drone while inspecting a railroad track.

The unconventional network is Ligado’s crown jewel as it seeks a dominant position in a new sector of the economy. As more Americans turn to the Internet of Things — a constellation of Web-enabled smart devices and appliances — to perform everyday tasks, the broadband provider that can support the constant flow of communications stands to make a great deal of money.

Other telecom companies have invested heavily in the Internet of Things, too. For instance, Verizon’s IoT division is nearly a billion-dollar business annually, according to its executives. But Ligado’s focus on industrial infrastructure is both demographically and geographically unique, Smith said.

“I think the requirements would be different,” he said. “If you go back to the rail example, there’s lots of miles of track that just don’t have any coverage on it today. So one of the first reasons [a traditional cellular carrier can’t operate there] is because it’s not there.”

As the first company to attempt a hybrid network using satellite airwaves, Ligado’s experiment is being closely watched by network operators and regulators around the world. But the company’s new strategy emerged after a long and difficult road.

LightSquared’s plans to build a nationwide 4G data network were foiled in 2012 when the Federal Communications Commission rescinded the company’s airwaves license, citing concerns by Deere, Garmin and other critics that transmissions over LightSquared’s satellite airwaves would interfere with GPS navigation devices.

At the time, Falcone, a former professional hockey player known on Wall Street for his competitive streak, had pledged a long-haul battle over the future of his company.

“One of the things I learned in hockey is that the game’s not over until the buzzer sounds at the end of the third period,” he told The Washington Post in 2012. “And until that buzzer sounds, you keep on playing as hard as you can.”

In 2012, the buzzer rang out. Already under financial pressure from creditors, LightSquared filed for bankruptcy protection, and a path to emerge only came clear in March 2015 when a number of investment firms, including Centerbridge Partners and Fortress Investment Group, proposed to take over from Falcone’s Harbinger Capital Partners. Under that deal, Falcone would retain a nonvoting stake in LightSquared. But he would lose the ability to litigate or negotiate with the GPS companies he blasted with a lawsuit in 2013 for allegedly standing in his way.

“Falcone was clearly a bomb-thrower — typical New York guy,” said one person familiar with the negotiations who spoke on the condition of anonymity because the talks were private. “He was just shotguns blazing, all hours of the day. And really, he probably could have done the same deal that Doug Smith did, if he had been willing to negotiate and compromise.”

The new management swiftly moved to defuse tension with the GPS industry. Knowing that LightSquared’s satellite airwaves were still intensely valuable, they named a former chairman of the FCC, Reed Hundt, to the board, as well as former Verizon chief executive Ivan Seidenberg. Together with Smith, the group devised a new approach — one that had the company making significant concessions.

Among the changes was a decision to drastically reduce LightSquared’s transmission power levels so that any data traveling over its airwaves would not jam the GPS signals. The firm agreed to clean up its signals so that less noise would spill over into the GPS industry’s back yard. And LightSquared committed to never using one of its satellite channels for ground-based purposes, ensuring a buffer between the GPS airwaves and the LightSquared airwaves.

“The new leadership is committed to a constructive approach to interference concerns,” said Jared Hendricks, a senior managing director at Centerbridge.

Days after formally exiting bankruptcy in December 2015, LightSquared announced it had reached a compromise with GPS industry officials. A couple of months later, the firm relaunched as Ligado — and has been hoping ever since for a green light from the FCC to begin building its cell towers.

By most measures, Ligado appears ready for takeoff once more. Deere did not respond to requests for comment and Garmin declined to do so. But other GPS industry officials say they are largely supportive of the changes the company has put in place, though some outstanding issues must still be negotiated.

“Discussions with Ligado have been constructive with the new leadership,” said Jim Kirkland, senior vice president and general counsel at Trimble, a GPS device maker that had clashed with LightSquared. “We’re happy we’re able to resolve some of the spectrum issues, and we’re committed to working with Ligado on the remaining issues.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.