Ancient Roman Glass Has Electronics Application

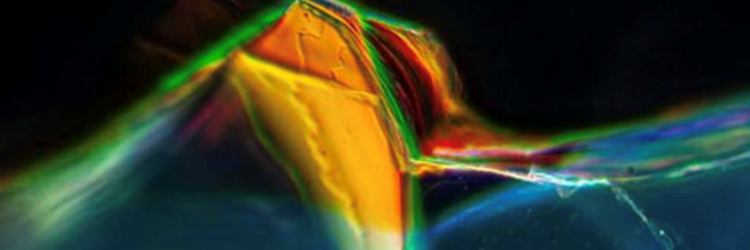

It’s beautiful. The brilliant colors of 2,000-year-old Roman glass fragments that were exposed to constant changes in temperature, moisture, and surrounding minerals, are now moving past use in jewelry as pendants or earrings and museum displays to applications in modern technology.

Fiorenzo Omenetto and Giulia Guidetti, engineering professors at the Tufts University Silklab noticed how molecules in the glass rearranged and recombined with minerals over thousands of years, forming photonic crystals that filter and reflect light in specific ways.

Photonic crystals can be used to create waveguides, optical switches, and other devices for fast optical communication. They can be engineered to block specific wavelengths of light while allowing others to pass through and can be used in filters, lasers, mirrors, and anti-reflection (stealth) devices.

Their research study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) USA. They report on the unique atomic and mineral structures that built up from the glass’ original silicate and mineral constituents, modulated by the pH of the surrounding environment and the fluctuating levels of groundwater in the soil.

The researchers say that the glass was a nanofabrication of photonic crystals by nature. The glass fragments date between the 1st century BCE and the 1st century CE, with origins from the sands of Egypt – an indication of global trade at the time. The bulk of the fragment preserved its original dark green color, but on its surface was a millimeter-thick patina that had an almost perfect mirror-like gold reflection. The patina had a hierarchical structure of highly regular, micrometer-thick silica layers of alternating high and low density, which resembled reflectors known as Bragg stacks. The vertical stacking of tens of Bragg stacks resulted in the golden mirror appearance of the patina.