Bacteria isn’t all bad. After all, the good bacteria are in our kombucha, yogurt, pickles, and sourdough bread. However, as “bad” bacteria become more resistant to antibiotics, the threat this poses grows.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a top global public health threat, directly killing approximately 1.27 million people in 2019 and contributing to 4.95 million deaths. Antimicrobials are medicines used to prevent and treat infections, including antibiotics.

A Columbia University study discovered that bacteria forming biofilms have a highly structured arrangement within that film, rather than the random groupings previously assumed.

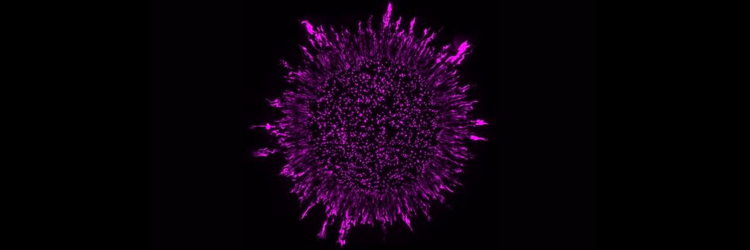

The team looked specifically at a common pathogen called Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Using scanning electron microscopy and fluorescence microscopy paired with cell labeling, the team discovered that P. aeruginosa in biofilms are packed lengthwise and arranged perpendicularly to their growth substrate. They also found that mutations modifying bacterial cell surfaces disrupt the arrangement.

When they tested the effects of sugar added from outside the biofilm, they found that the biofilm’s anatomy affected the responsiveness and distribution of the sugar.

“There’s a yin-yang trade-off for bacteria that form biofilms, since the biofilm guards against antibiotics and other threats, but also prevents food from entering and feeding the system,” said Professor Lars Dietrich, a lead author on the paper. Hannah Dayton, a graduate student, spearheaded the research.

Mutant bacteria with a disordered cellular arrangement were more responsive to the sugar or antibiotic in areas called subzones. They also showed that those changes in the biofilm anatomy shift the peak metabolic activity in the structure.

This means that some areas in those groupings can be manipulated into being more responsive to antibiotics rather than less. The biofilm microstructure can be tuned to influence the metabolism of bacterial subpopulations and affect the group’s overall survival.

These findings have implications for treating infections caused by P. aeruginosa and other biofilm-forming pathogens.

The team published the study in the journal PLOS Biology.