Brain-computer interfaces just got closer

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) assistive devices may one day help people with brain or spinal injuries to move or communicate. BCI systems depend on implantable sensors that record electrical signals in the brain and use those signals to drive external devices like computers or robotic prosthetics. So far, the most common of these BCI systems uses one or two sensors to sample up to a few hundred neurons. Neuroscientists are interested in much larger groups of brain cells.

The team of researchers from Brown, Baylor University, University of California at San Diego and Qualcomm, began the work of developing system approximately four years ago. The challenge was two-fold:

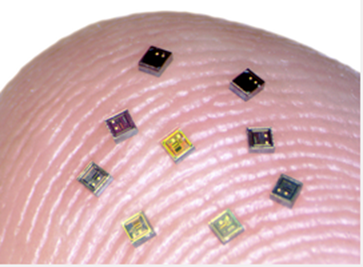

- Shrink the complex electronics involved in detecting, amplifying and transmitting neural signals into the tiny silicon neurograin chips

- Develop the body-external communications hub that receives signals from the tiny chips

The device is a patch the size of a thumbprint, that attaches to the scalp and works like a miniature cell phone tower, employing a network protocol to coordinate the signals from the neurograins, each of which has its own network address. The patch also supplies wireless power to the neurograins.

In a study published on August 12 in Nature Electronics, the research team demonstrated the use of nearly 50 autonomous neurograins to record neural activity in a rodent. The results could one day enable the recording of brain signals in unprecedented detail, leading to new insights into how the brain works and new therapies for people with brain or spinal injuries.

Original Release: Eureka Alert