Do you know the coolest spot in the universe?

Ever wondered where the coolest place in the universe is? Well in terms of temperature, NASA is creating the coolest spot in the universe, this summer, by sending an ice chest-sized box to the International Space Station.

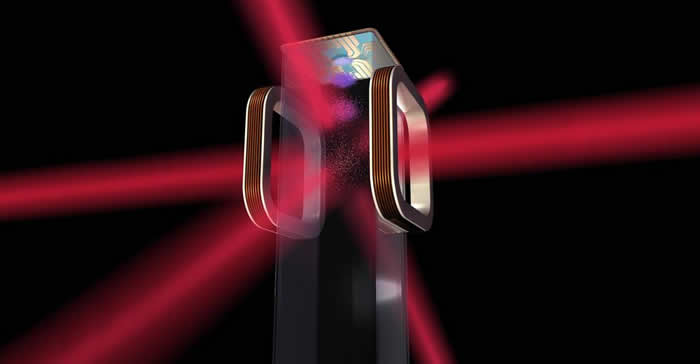

What will be inside that box I hear you ask? Inside that box will be; lasers, a vacuum chamber and an electromagnetic ‘knife’ to cancel out the energy of gas particles, slowing them until they’re almost motionless.

This suite of instruments is called the Cold Atom Laboratory (CAL), and was developed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. CAL is in the final stages of assembly at JPL, ahead of a ride to space this August on SpaceX CRS-12.

Its instruments are designed to freeze gas atoms to a mere billionth of a degree above absolute zero. That’s more than 100 million times colder than the depths of space.

“Studying these hyper-cold atoms could reshape our understanding of matter and the fundamental nature of gravity,” said CAL Project Scientist Robert Thompson of JPL. “The experiments we’ll do with the Cold Atom Lab will give us insight into gravity and dark energy – some of the most pervasive forces in the universe.”

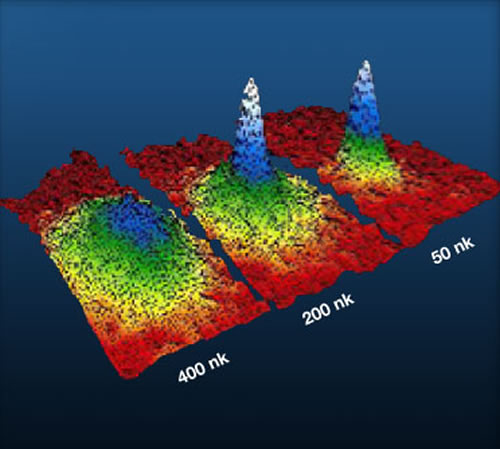

When atoms are cooled to extreme temperatures, as they will be inside of CAL, they can form a distinct state of matter known as a Bose-Einstein condensate. In this state, familiar rules of physics recede and quantum physics begins to take over. Matter can be observed behaving less like particles and more like waves. Rows of atoms move in concert with one another as if they were riding a moving fabric. These mysterious waveforms have never been seen at temperatures as low as what CAL will achieve.

NASA has never before created or observed Bose-Einstein condensates in space. On Earth, the pull of gravity causes atoms to continually settle towards the ground, meaning they’re typically only observable for fractions of a second.

But on the International Space Station, ultra-cold atoms can hold their wave-like forms longer while in free-fall. That offers scientists a longer window to understand physics at its most basic level. Thompson estimated that CAL will allow Bose-Einstein condensates to be observable for up to five to 10 seconds; future development of the technologies used on CAL could allow them to last for hundreds of seconds.

Bose-Einstein condensates are a ‘superfluid’ – a kind of fluid with zero viscosity, where atoms move without friction as if they were all one, solid substance.

“If you had superfluid water and spun it around in a glass, it would spin forever,” said Anita Sengupta of JPL, Cold Atom Lab Project Manager. “There’s no viscosity to slow it down and dissipate the kinetic energy. If we can better understand the physics of superfluids, we can possibly learn to use those for more efficient transfer of energy.”

Five scientific teams plan to conduct experiments using the Cold Atom Lab. Among them is Eric Cornell of the University of Colorado, Boulder and the National Institute for Standards and Technology. Cornell is one of the Nobel Prize winners who first created Bose-Einstein condensates in a lab setting in 1995.

The results of these experiments could potentially lead to a number of improved technologies, including sensors, quantum computers and atomic clocks used in spacecraft navigation.

Especially exciting are applications related to dark energy detection, said Kamal Oudrhiri of JPL, the CAL deputy project manager. He noted that current models of cosmology divide the universe into roughly 27% dark matter, 68% dark energy and about five percent ordinary matter.

“This means that even with all of our current technologies, we are still blind to 95% of the universe,” Oudrhiri said. “Like a new lens in Galileo’s first telescope, the ultra-sensitive cold atoms in the Cold Atom Lab have the potential to unlock many mysteries beyond the frontiers of known physics.”

The Cold Atom Lab is currently undergoing a testing phase that will prepare it prior to delivery to Cape Canaveral, Florida.

“The tests we do over the next months on the ground are critical to ensure we can operate and tune it remotely while it’s in space, and ultimately learn from this rich atomic physics system for years to come,” said Dave Aveline, the test-bed lead at JPL.

JPL is developing the Cold Atom Laboratory, sponsored by the International Space Station Program at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.