In research that could lead to better gas mask filters, scientists at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have been putting the X-ray spotlight on composite materials in respirators used by the military, police, and first responders, and the results have been encouraging.

What they are learning not only provides reassuring news about the effectiveness of current filters in protecting people from lethal compounds such as VX and sarin, but they also provide fundamental information that could lead to more advanced gas masks as well as protective gear for civilian applications.

The project at Berkeley Lab is led by Hendrik Bluhm, a senior staff scientist with joint appointments in the Chemical Sciences Division and the Advanced Light Source (ALS). On his team are two postdoctoral researchers in the Chemical Sciences Division, Lena Trotochaud and Ashley Head. The Berkeley Lab team is part of a larger collaboration that includes researchers at the University of Maryland at College Park, Johns Hopkins University, and the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory.

The researchers pointed out that studying how metal oxides interact with small organophosphates could be relevant beyond the gas masks used by the military and emergency responders. The work they are doing could have applications in sensing technologies. In addition, less potent forms of organophosphates are widely used as pesticides and herbicides, so the findings could help the agricultural industry and environmental scientists understand what eventually happens to these substances after they are released into the environment.

“This is a project where we are working to help save lives,” said Trotochaud. “That is very fulfilling.”

For Head, the project provided a particularly relevant topic of conversation at family gatherings.

“My sister-in-law is in the Air Force,” said Head. “I was telling her what I do, and she said, ‘When I’m deployed, I get a gas mask. Does it work?’ She tells her colleagues about what I’m working on. So much of what we do in basic science is far removed from an application. While our work is still fundamental, I can now tell my family what I’m doing, and they’ll actually understand.”

Do the masks work?

Current gas mask filters do counter current threats, but there are large gaps in knowledge about how they do so at the molecular level, the researchers said. The question comes up because many of the filters were developed to handle a wide range of ever-changing chemical threats and to work under a variety of different conditions all over the world. During World War I, chemical warfare agents were predominantly chlorine and mustard gases.

Since then, a new class of chemical weapon came onto the scene. Sarin and venomous agent X, or VX, are nerve agents so named because they interfere with the nervous system’s ability to communicate with muscles, including those that control breathing. The current materials used in gas mask filters provide effective protection against all of these compounds, despite the very different chemical properties of the gases.

Gas mask filters include activated carbon, a family of absorbents that trap toxins in millions of micro-pores. It is the same compound used to filter water and treat ingestion of poisons. The activated carbon traps the toxins, but in gas masks it is further augmented with metal oxides, such as copper and molybdenum, to help break down the toxins.

“Even though the first gas mask filters were developed before these new nerve agents emerged, the current filters are effective at capturing them, and they also seem to be good at breaking them down, but we still have some questions about the chemistry of this process,” said Trotochaud. “We know it works, but we don’t always know how it fails. We do know the filters sometimes stop working after a while when exposed to these organophosphorus compounds, so the chemistry of how the material is deactivated after exposure to these agents is a big part what we’re studying.”

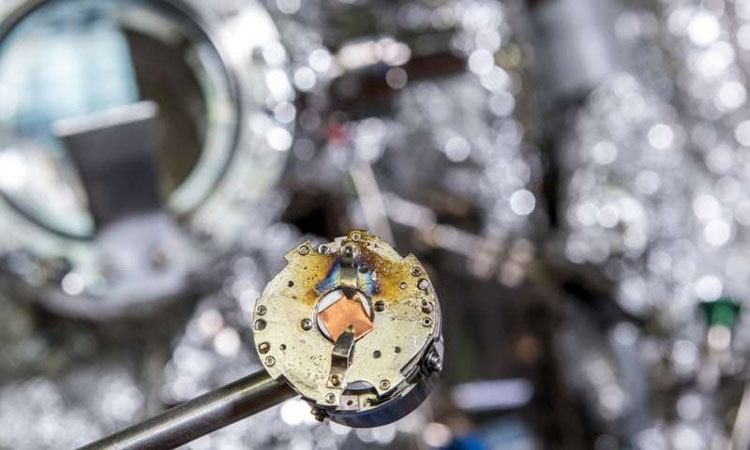

The Berkeley Lab researchers targeted two metal oxides – molybdenum oxide and copper oxide – that are key working components in gas mask filters. To simulate the small organophosphorus molecules of sarin and VX, the researchers worked with dimethyl methylphosphonate (DMMP), an established proxy for sarin with similar functional groups but significantly lower toxicity.

The goal is to better understand the molecular interactions that occur as various gases are adsorbed by the gas mask filter materials, and the environmental conditions – air pollution, diesel fuel exhaust, water – that could alter performance and shelf life, so even better materials can be developed.

“Much of our early work focused on characterization,” said Bluhm, the project’s principal investigator. “There were a lot of details to resolve. What exactly does copper oxide do? What does molybdenum oxide do? Why does one behave differently than the other? Understanding where the differences are can make these filtration materials potentially much more efficient.”

The effects of water vapor were of particular interest because of how the masks are used, noted Bluhm.

“It’s a filtration mask that sits in front of our mouths, so there is high humidity as we breathe into it,” he said. “Among the published findings from our project is that water vapor seems to be neutral or even beneficial for the performance of the materials.”

This was reported in a 2016 study, which found that water exposure activated the composite surface in a way that facilitated the binding of the DMMP molecule, lowering the energy required to break the molecule down.