Helping the microchip industry go with the flow

A new study by scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has uncovered a source of error in an industry-standard calibration method that could lead microchip manufacturers to lose a million dollars or more in a single fabrication run. The problem is expected to become progressively more acute as chipmakers pack ever more features into ever smaller space.

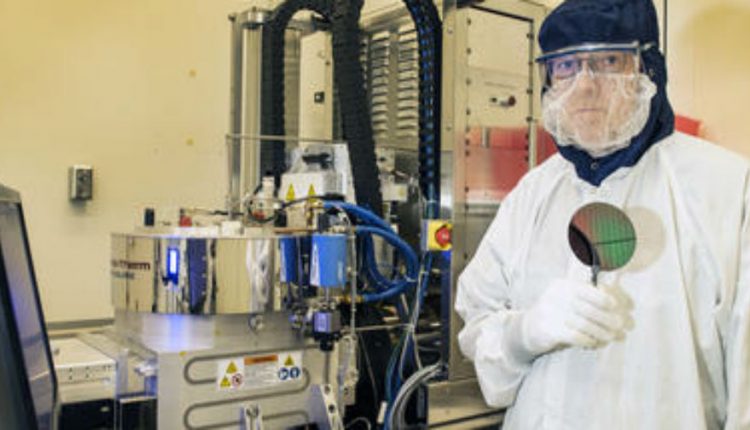

The error occurs when measuring very small flows of exotic gas mixtures. Small gas flows occur during chemical vapor deposition (CVD), a process that occurs inside a vacuum chamber when ultra-rarefied gases flow across a silicon wafer to deposit a solid film. CVD is widely used to fabricate many kinds of high-performance microchips containing as many as several billion transistors. CVD builds up complex 3D structures by depositing successive layers of atoms or molecules; some layers are only a few atoms thick. A complementary process called plasma etching also uses small flows of exotic gases to produce tiny features on the surface of semiconducting materials by removing small amounts of silicon.

The exact amount of gas injected into the chamber is critically important to these processes and is regulated by a device called a mass flow controller (MFC). MFCs must be highly accurate to ensure that the deposited layers have the required dimensions. The potential impact is large because chips with incorrect layer depths must be discarded.

“Flow inaccuracies cause nonuniformities in critical features in wafers, directly causing yield reduction,” said Mohamed Saleem, Chief Technology Officer at Brooks Instrument, a U.S. company that manufactures MFCs among other precision measurement devices. “Factoring in the cost of running cleanrooms, the loss on a batch of wafers scrapped due to flow irregularities can run around $500,000 to $1,000,000. Add to that cost the process tool downtime required for troubleshooting, and it becomes prohibitively expensive.”

Modern nanofabrication facilities cost several billion dollars each, and it is generally not cost-effective for a company to constantly fine tune CVD and plasma etching. Instead, the facilities rely on accurate gas flows controlled by MFCs. Typically, MFCs are calibrated using the “rate of rise” (RoR) method, which makes a series of pressure and temperature measurements over time as gas fills a collection tank through the MFC.

“Concerns about the accuracy of that technique came to our attention recently when a major manufacturer of chip-fabrication equipment found that they were getting inconsistent results for flow rate from their instruments when they were calibrated on different RoR systems,” said John Wright of NIST’s Fluid Metrology Group, whose members conducted the error analysis.