According to the researchers at the University of Washington, the virus that causes hepatitis C protects itself by blocking signals that call up immune defenses in liver cells.

“The finding helps explain why many patients fail certain drug treatments, and should help develop more effective alternate treatment protocols,” said Ram Savan, the study’s Corresponding Author and an Assistant Professor of immunology in the UW School of Medicine.

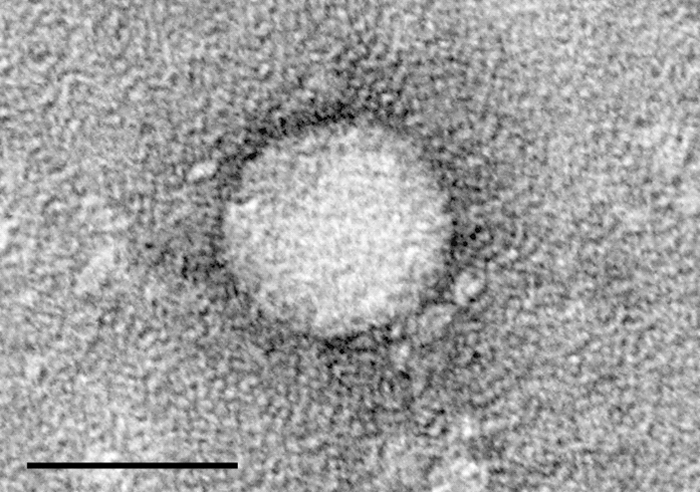

The most common cause of chronic hepatitis is the hepatitis C virus, as well as the leading cause of liver cancer in the US. Contact with infected blood is how it’s primarily spread, and each year more than 30,000 Americans become infected.

As many as 85% develop life-long chronic infections, and of these patients, about one in 10 will eventually develop cirrhosis and liver cancer.

In the latest study, lead author Abigail Jarret, now a graduate student at Yale University, and her group showed that hepatitis C virus sabotages the antiviral defenses of liver cells by blunting the effect of key immune proteins called interferons.

When cells become infected, they release interferons. These in turn spur hundreds of genes that generate virus-fighting proteins within the cell. Interferons can even provoke cells to self-destruct to prevent the virus from propagating.

One of these interferons, called interferon-alpha, has been used for many years to treat chronic hepatitis C virus infections, either alone or in concert with an antiviral called ribavirin. These treatments helped many patients get rid of the virus, but the treatment fails to cure more than 60% of patients.

Newer, more effective drugs with fewer side effects have now largely replaced interferon-based therapies. However, it was not clear why interferon treatment failed so often. From this study, researchers hypothesized that the virus’ ability to evade interferons was related to the cells themselves.

In a previous study, Savan’s research team discovered that when hepatitis C virus invades a liver cell, the virus induces the cell to activate two genes—MYH7 and MYH7B. These genes are usually active only in smooth skeletal muscle and heart cells. Once activated, these genes produce two microRNAs, molecules that can interfere with the production of other proteins.

Savan and his fellow researchers showed that these microRNAs interfered with the cell’s production of two interferons. By activating the MYH7 and MYH7B genes, the invading hepatitis C viruses limit liver cells’ ability to generate these interferons. The cells are then less able to resist and remove the virus.

Jarret explained that the study also showed that these virally-induced microRNAs deter production of a receptor crucial to the cell’s interferon-driven antiviral response. Therefore these hepatitis C virus-induced microRNAs can blunt liver cell interferon-driven antiviral defenses in two ways.

First, the virus inhibits the cell’s ability to produce its own type III interferons. Second, it prevents the cells from making the receptors needed in order for type I interferons to be effective.

Jarret concluded: “This may in part explain why interferon treatments, which harness a type I interferon, fail in so many patients.”

More information: MedicalXpress

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.