Jupiter’s Aurora Created by Alternating Rather than Direct Currents

By Ruth Seeley

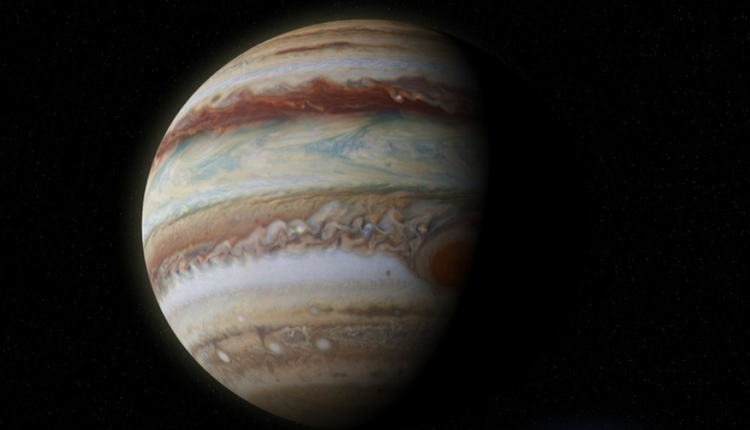

The largest planet in the solar system also has the brightest aurora, with a radiant power of 100 terawatts. It would take 100,000 power plants to produce this light. Jupiter’s auroras, like Earth’s, display themselves as two huge oval rings around the poles. Driven by a gigantic system of electrical currents that connects the polar light region with Jupiter’s magnetosphere—the region around a planet influenced by its magnetic field—most of the electric currents run along Jupiter’s magnetic field lines, also known as Birkeland currents.

The planet’s electric current system features large centrifugal forces that hurl ionized sulfur dioxide gas from its moon Io through the magnetosphere. Io, which is volcanically active, produces one ton of sulfur dioxide gas per second, which ionizes into Jupiter’s magnetosphere. Now, using data transmitted by NASA’s Juno spacecraft, an international team of researchers has measured the current system responsible for Jupiter’s aurora and shown that the direct currents were much weaker than expected and alternating currents must, therefore, play a special role. (On Earth, on the other hand, a direct current system creates its aurora.)

Professor Dr. Joachim Saur from the Institute of Geophysics and Meteorology at the University of Cologne said, “Jupiter’s electric current systems are driven by the enormous centrifugal forces in Jupiter’s rapidly rotating magnetosphere. Because of Jupiter’s fast rotation—a day on Jupiter lasts only 10 hours—the centrifugal forces move the ionized gas in Jupiter’s magnetic field, which generates the electric currents.”

NASA’s Juno spacecraft has been in polar orbit around Jupiter since July 2016. Its goal is to better understand the interior and aurora of Jupiter, and it has now measured the electric direct current system responsible for Jupiter’s aurora. Scientists measured the magnetic field environment of Jupiter with high precision to derive the electric currents. The total current is approximately 50 million amperes. However, this value is clearly below the theoretically expected values. Small-scale, turbulent alternating currents (also referred to as Alfvenic currents), which have so far received little attention, account for these deviations.

“These observations, combined with other Juno spacecraft measurements, show that alternating currents play a much greater role in generating Jupiter’s aurora than the direct current system,” Saur said.

The results of Saur’s research were recently published in Nature Astronomy.

Source: University of Cologne