What do monkeys, guinea pigs and native English speakers have in common?

The answer? Specific speech sounds stimulate the same region in the brain of humans, macaques and guinea pigs according to a University of Pittsburgh research report published in the journal eNeuro.

The brain’s responses to sound can be recorded from small electrodes placed on a person’s scalp and are used to quickly assess a child’s hearing capacity and flag potential speech and language disorders. The downside is that the method lacks specificity.

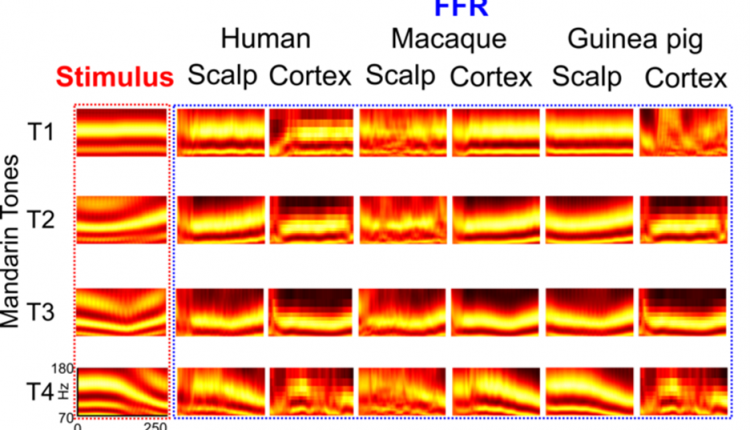

The brain’s responses to sound—called frequency-following responses, or FFRs show up on a neurotypical brain electroencephalogram as a near carbon copy of the sound wave that the brain interprets and responds to. They have the potential to complement hearing screening of newborns. They are also used to identify any issues in auditory processing, or the way that the brain interprets sounds coming from the environment, especially speech.

Until recently, scientists thought that FFRs arise deep inside the brain stem—the brain’s innermost structures close to the base of the skull—and ripple outward. The researchers proved the long-standing theory wrong. Instead, FFRs are generated not only at the brain stem, but also in the auditory cortex of the brain—the region responsible for the processing of sounds located right around the temple and that the pattern of FFR generation is similar across mammals.

This is where the three are similar–in response to four different tones of the Mandarin syllable “yi,” the brains of English-speaking individuals unfamiliar with Mandarin Chinese generated similar FFRs as macaque monkeys and guinea pigs, both of which have very similar hearing range and sensitivity to humans.

Between 5% and 10% of Americans have diagnosed communication disorders. A better understanding of the way auditory deficits manifest in the brain can fill a critical gap in the development of fast, accurate and non-invasive diagnostics.

Original Release: Eureka Alert