As our need for battery power increases and the amount of space available to generate and contain that power decreases, ultrathin batteries are in high demand, particularly for use in medical monitoring devices.

Recently a scientific team from the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Vanderbilt University has made the first experimental observation of a material phase that had been predicted but never seen. The newly discovered phase couples with a known phase to enable unique control over material properties—an advance that paves the way to eventual manipulation of electrical conduction in two-dimensional (2D) materials such as graphene and could pave the way for a new way to create ultrathin batteries.

The team made the discovery using a layered, copper-containing crystal that is ferroelectric, or has a constant electric dipole that can be reversed when an electric field is applied.

“These materials may become building blocks of ultrathin energy and electronics technologies,” said ORNL’s Nina Balke, a corresponding author of a paper reporting the finding in Nature Materials.

The observation shows properties that can be harnessed to provide materials with new functions. These properties depend on the locations of copper atoms in the crystal. The copper atoms can either sit within the layers of the crystal or become displaced into the gaps between layers—called “van der Waals gaps”—where they make weak ionic bonds with neighboring layers and form the new phase.

The scientists measured electromechanical responses throughout layered ferroelectric crystals of copper indium thiophosphate, or CIPS. This material is piezoelectric, meaning its surfaces become charged when it is stretched or squeezed. Conversely, applying an electric field makes a piezoelectric material expand or contract. The piezoelectric properties of CIPS were the key to studying it experimentally as well as theoretically to reveal the new phenomena.

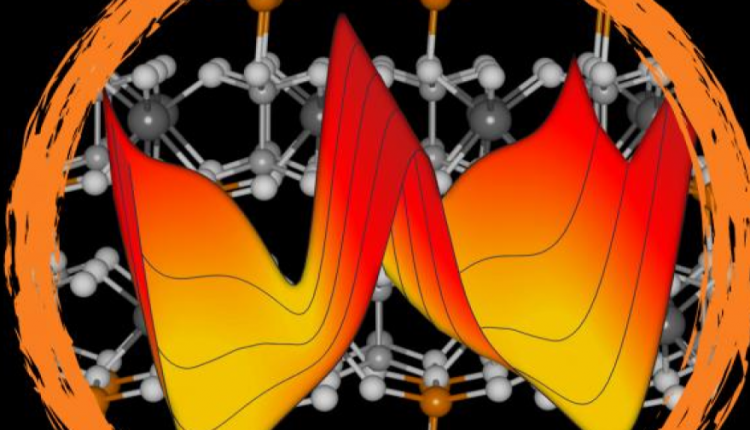

The theoretical research was carried out by the group of Sokrates Pantelides, a professor at Vanderbilt University and distinguished visiting scientist at ORNL. Using quantum calculations, group members moved the atom responsible for polar displacement—copper—through the crystal structure and calculated the potential energy. “A typical outcome for a ferroelectric material is that you have two energy minima, or ‘wells,’ for this atom; each one represents a polarization vector, one pointing up, the other down,” said Pantelides. “For this material, theory predicted four energy minima, which is extremely unusual.”

The research team found that the two additional energy minima arise from a second structural phase with double the polarization amplitude and with a stable position for the copper atom in the van der Waals gap. Moreover, the theoretically predicted piezoelectric constants for the two polar phases in CIPS matched the experimentally measured ones.

“This is the first reported observation of the piezoelectric and ferroelectric properties of the high-polarization phase,” said Balke, the leading experimentalist on the team. “It was known that copper can go in the gap, but the consequences for piezoelectric and ferroelectric properties were not known. But in the end, that’s what forms the quadruple well.”

Sabine Neumayer, a member of the ORNL team, added, “The quadruple well opens up a lot of exciting opportunities, especially because we can control transitions between these four different polarization states using temperature, pressure and electric fields.” Usually, ferroelectrics are thought of as switches between two states. In CIPS, four states are accessible.

“CIPS is one of the first ferroelectric materials that is natively compatible with nearly all 2D materials because of its van der Waals structure. Anytime you have van der Waals forces, it means that you can put 2D materials together and separate them without causing major structural damage,” Peter Maksymovych, another corresponding author, said. “The van der Waals structure is what enables cleaving of bulk crystals to create 2D nanostructures with clean surfaces.”

Scientists worldwide have been racing to create an active interface for 2D materials like graphene, a single-atom-thick material with very high electron mobility. “We imagine that in the future, an active interface to CIPS can control graphene via piezoelectric, ferroelectric and other responsive properties,” Maksymovych said. “It’ll put the smarts into graphene.”

Michael McGuire in ORNL’s Materials Science and Technology Division grew and characterized the study’s crystals with Michael Susner, now at the Air Force Research Laboratory. “The competition and coexistence of multiple phases in the crystals makes these materials particularly exciting and interesting,” he said. “The ability to study complex materials like these both theoretically and experimentally over a wide range of length scales with complementary techniques makes this type of work possible at ORNL.”

The researchers ran experiments at ORNL’s Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences. The experiments relied on piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM) to image and control ferroelectric domains on scales of millionths to billionths of meters. A sharp conductive probe applies an electric field to a sample’s surface, and the material’s electromechanically induced deformation is inferred from the probe’s displacement.

In future studies, the researchers will probe dynamic properties: observing ratios of high and low polarization in strained materials; moving, stabilizing and embedding atoms of the new phase to make a switch; experimentally probing predicted behavior of materials under pressure; and studying how ferroelectric domains reorient after an electric field is applied.

Source: Oak Ridge National Laboratory