Researchers from Stanford University have just created a low-cost plastic material that could be used to develop clothing that cools the wearer and as a result reduces the need for energy-consuming air conditioning.

If the material is woven into clothing it has the ability to cool the body more efficiently than is possible with the natural or synthetic fabrics, like the ones found in our clothing today, according to the Stanford team.

The researchers suggest that this new family of fabrics could be used to to create garments that keep people cool in hot climates, where air conditioning is scarce.

“If you can cool the person rather than the building where they work or live, that will save energy,” said Yi Cui, an associate professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford and of photon science at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

How it works

The material works by allowing the body to discharge heat in two ways. These discharges actually make the wearer feel nearly 4º F t cooler than if he or she wore cotton clothing.

The cooling happens as perspiration evaporates through the material, which is something ordinary fabrics already do. However, the Stanford material then employs its second, novel cooling mechanism, which allows heat that the body emits as infrared radiation to pass through the plastic textile.

All objects. even our bodies, release heat in the form of infrared radiation. The reason blankets keep us warm is because they trap the infrared heat emissions close to the body. This thermal radiation escaping from our bodies is also what makes us visible in the dark through night-vision goggles.

“Forty to 60% of our body heat is dissipated as infrared radiation when we are sitting in an office,” said Shanhui Fan, a professor of electrical engineering who specializes in photonics, which is the study of visible and invisible light. “But until now there has been little or no research on designing the thermal radiation characteristics of textiles.”

How they did it

To develop the cooling textile, the researchers combined nanotechnology, photonics and chemistry in order to give polyethylene – the clear, clingy plastic we use as kitchen wrap – new characteristics that would be desirable in clothing material: allowing thermal radiation, air and water vapor to pass right through, and making it opaque to visible light.

The easiest attribute was allowing infrared radiation to pass through the material, because this is a characteristic of ordinary polyethylene food wrap. Of course, kitchen plastic is impervious to water and is see-through as well, rendering it useless as clothing.

The future of clothing

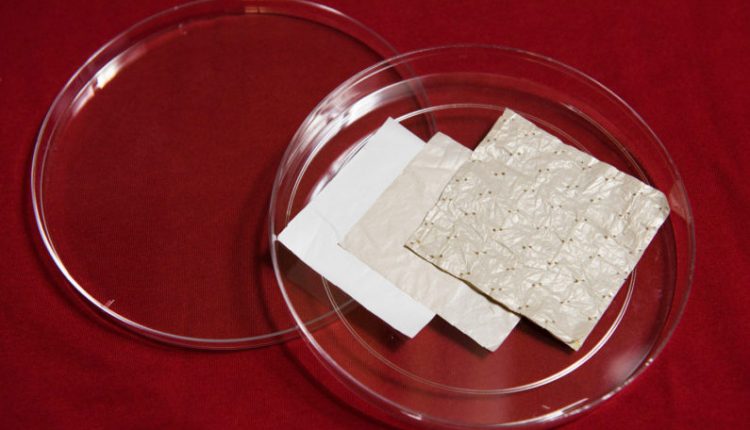

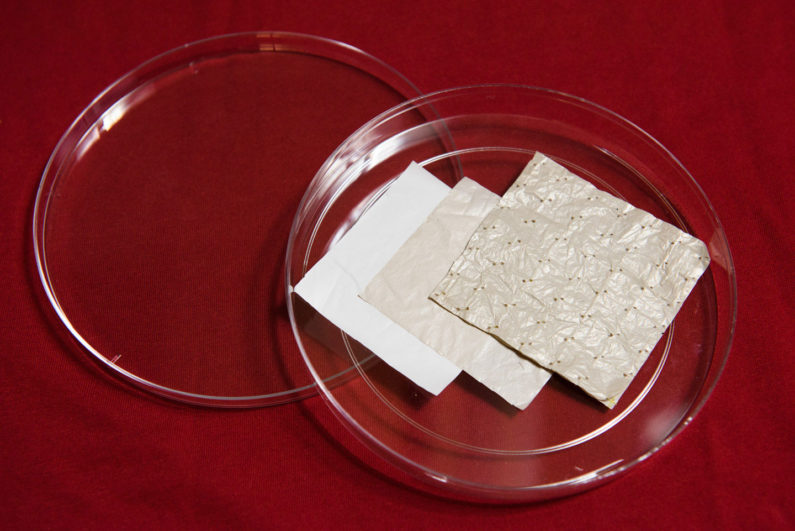

What the researchers were left with was a single-sheet material that met their three basic criteria for a cooling fabric. To make this thin material more fabric-like, they created a three-ply version: two sheets of treated polyethylene separated by a cotton mesh for strength and thickness.

“Wearing anything traps some heat and makes the skin warmer,” Fan said. “If dissipating thermal radiation were our only concern, then it would be best to wear nothing.”

When they tested the material against other fabrics, the researchers found that cotton fabric made the skin surface 3.6º F warmer than their cooling textile. They say that this difference means that a person dressed in their new material might feel not want to turn on an air conditioner or fan.

The researchers will continue their work by adding more colors, textures and cloth-like characteristics to the material.

“If you want to make a textile, you have to be able to make huge volumes inexpensively,” said Cui.

According to Fan, this research opens up new ideas about how we cool or heat things, passively, without the use of outside energy.

“In hindsight, some of what we’ve done looks very simple, but it’s because few have really been looking at engineering the radiation characteristics of textiles,” said Fan.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.