Researchers extend the capabilities of Two-Photon Lithography (TPL)

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) researchers have discovered novel ways to extend the capabilities of Two-Photon Lithography (TPL), a high-resolution 3D printing technique capable of producing nanoscale features smaller than one-hundredth the width of a human hair.

The findings, recently published on the cover of the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, also unleashes the potential for X-rayComputed Tomography (CT) to analyze stress or defects noninvasively in embedded 3D-printed medical devices or implants.

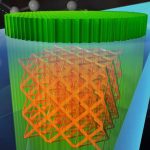

Two-photon lithography typically requires a thin glass slide, a lens and an immersion oil to help the laser light focus to a fine point where curing and printing occurs. It differs from other 3D-printing methods in resolution, because it can produce features smaller than the laser light spot, a scale no other printing process can match. The technique bypasses the usual diffraction limit of other methods because the photoresist material that cures and hardens to create structures—previously a trade secret—simultaneously absorbs two photons instead of one.

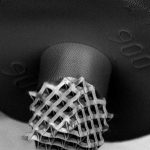

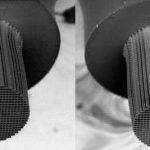

In the paper, LLNL researchers describe cracking the code on resist materials optimized for two-photon lithography and forming 3D microstructures with features less than 150nm. Previous techniques built structures from the ground up, limiting the height of objects because the distance between the glass slide and lens is usually 200 microns or less. By turning the process on its head—putting the resist material directly on the lens and focusing the laser through the resist—researchers can now print objects multiple millimeters in height. Furthermore, researchers were able to tune and increase the amount of X-rays the photopolymer resists could absorb, improving attenuation by more than ten times over the photoresists commonly used for the technique.

“In this paper, we have unlocked the secrets to making custom materials on two-photon lithography systems without losing resolution,” said LLNL researcher James Oakdale, a co-author on the paper.

Because the laser light refracts as it passes through the photoresist material, the linchpin to solving the puzzle, the researchers said, was “index matching” – discovering how to match the refractive index of the resist material to the immersion medium of the lens so the laser could pass through unimpeded. Index matching opens the possibility of printing larger parts, they said, with features as small as 100nm.

“Most researchers who want to use two-photon lithography for printing functional 3D structures want parts taller than 100 microns,” said Sourabh Saha, the paper’s lead author. “With these index-matched resists, you can print structures as tall as you want. The only limitation is the speed. It’s a tradeoff, but now that we know how to do this, we can diagnose and improve the process.”

By tuning the material’s X-ray absorption, researchers can now use X-ray-computed tomography as a diagnostic tool to image the inside of parts without cutting them open or to investigate 3D-printed objects embedded inside the body, such as stents, joint replacements or bone scaffolds. These techniques also could be used to produce and probe the internal structure of targets for the National Ignition Facility, as well as optical and mechanical metamaterials and 3D-printed electrochemical batteries.

The only limiting factor is the time it takes to build, so researchers will next look to parallelize and speed up the process. They intend to move into even smaller features and add more functionality in the future, using the technique to build real, mission-critical parts.

“It’s a very small piece of the puzzle that we solved, but we are much more confident in our abilities to start playing in this field now,” Saha said. “We’re on a path where we know we have a potential solution for different types of applications. Our push for smaller and smaller features in larger and larger structures is bringing us closer to the forefront of scientific research that the rest of the world is doing. And on the application side, we’re developing new practical ways of printing things.”