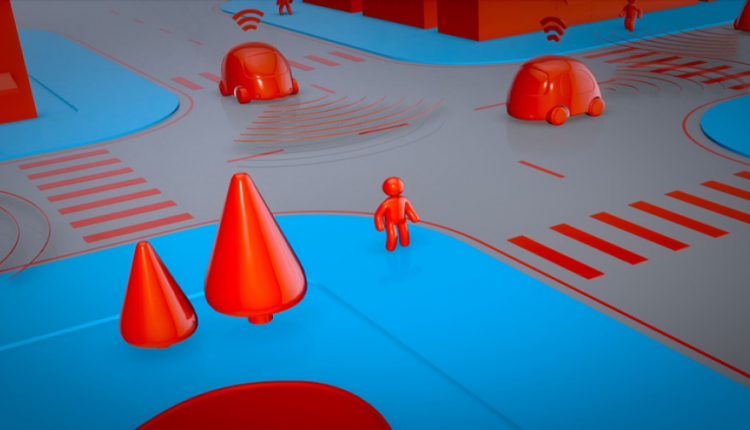

Sight-Correcting System and Humans Teach Autonomous Vehicles How to Drive

The human/autonomous vehicle relationship is, at this point, quite symbiotic: some researchers are creating algorithms so self-driving cars can understand, predict, and adjust for human behavior, like MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, which is working to classify the “social personalities” of other drivers on the road so autonomous vehicles can avoid accidents.

Recently, researchers from Deakin University in Australia published results of a study of imitation learning or learning from demonstration in IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica, a joint publication of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) and the Chinese Association of Automation. They concluded that with the help of an improved sight-correcting system, self-driving cars could learn just by observing human operators complete the same task.

A human operator drives a vehicle outfitted with three cameras, observing the environment from the front and each side of the car. The data is then processed through a neural network — a computer system based on how the brain’s neurons interact to process information — that allows the vehicles to make decisions based on what it learned from watching the human make similar decisions.

“The expectation of this process is to generate a model solely from the images taken by the cameras,” said paper author Saeid Nahavandi, Alfred Deakin Professor, pro vice-chancellor, chair of engineering and director for the Institute for Intelligent Systems Research and Innovation at Deakin University. “The generated model is then expected to drive the car autonomously.”

The processing system is specifically a convolutional neural network, which is mirrored on the brain’s visual cortex. The network has an input layer, an output layer and any number of processing layers between them. The input translates visual information into dots, which are then continuously compared as more visual information comes in. By reducing the visual information, the network can quickly process changes in the environment: a shift of dots appearing ahead could indicate an obstacle in the road. This, combined with the knowledge gained from observing the human operator, means that the algorithm knows that a sudden obstacle in the road should trigger the vehicle to fully stop to avoid an accident.

“Having a reliable and robust vision is a mandatory requirement in autonomous vehicles, and convolutional neural networks are one of the most successful deep neural networks for image processing applications,” Nahavandi said.

He noted a couple of drawbacks, however. One is that imitation learning speeds up the training process while reducing the amount of training data required to produce a good model. In contrast, convolutional neural networks require a significant amount of training data to find an optimal configuration of layers and filters, which can help organize data.

“For example, we found that increasing the number of filters does not necessarily result in a better performance,” Nahavandi said. “The optimal selection of parameters of the network and training procedure is still an open question that researchers are actively investigating worldwide.” Next, the researchers plan to study more intelligent and efficient techniques, including genetic and evolutionary algorithms to obtain the optimum set of parameters to better produce a self-learning, self-driving vehicle.