We are now in a generation where cities across the world are actively welcoming ‘smart’ technologies to improve the quality of life for their citizens, whether that is through improving traffic patterns, to energy savings or even reducing noise pollution.

However with costs and maintenance standing in the way, are there existing resources that could be deployed to bring about the same benefits to communities of the smart city movement?

Data in the smart cities

University at Albany researcher Tolga Soyata and a team of students looked at one possible solution in a new study.

They found that technology found in our phones and tablets have the capability to cover about two-thirds of the data that smart cities currently collect through dedicated sensors.

By applying a mobile crowd-sensing (MCS) approach, communities may have the capability to transmit the same amount of data, with virtually the same level of accuracy.

Published on December 1st 2017, in the issue of IEEE Sensors Journal, Soyata and his students review the types of smart technologies currently deployed in cities, which break down into two primary categories: dedicated and non-dedicated sensors, the latter being available as a built-in capability in every smartphone.

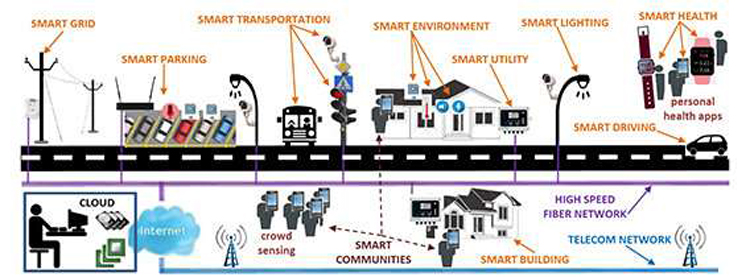

Most communities use a combination of cameras, microphones, temperature sensors, GPS devices and RFID (radio frequency identification) technology to monitor traffic, weather and energy consumption.

These devices in turn supply data that makes it easier to track utilities, lighting, parking, health and the environment.

But among the key drawbacks to dedicated sensors are higher deployment and maintenance costs.

And yet, almost all of the data cities collect can also be captured by our smartphones.

Is it trustworthy?

The question becomes, can we trust the captured data, and protect the privacy of users who might be supplying information in lieu of a dedicated sensor network?

“The MCS concept also has known implementation challenges, such as incentivizing the crowd and ensuring the trustworthiness of the captured data, and covering a wide sensing area,” said Soyata, an associate professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering in the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

“Considering the pros and cons of each option, the decision as to which one is better becomes a non-trivial answer. In this paper, we conduct a thorough study of both types of sensors and draw conclusions about which one becomes a favorable option based on a given application platform.”

For instance, while one smart device delivering data might diverge by up to 10% of dedicated sensors, as more users are added, the cumulative information was found to be within a percentage point.

According to the Mobility Report by Ericsson.com, there could be as many as 6.1 billion smart phones in circulation by 2020.

That’s a vast number of potential data collectors for communities large and small. But smart phones aren’t quite a catch-all answer for the type of data dedicated sensors currently provide.

“We show that while all sensors are available in dedicated form, about two-thirds are available in non-dedicated form,” said Soyata.

Still, the potential impact of non-dedicated sensors to make cities more efficient and improve the lives of residents is substantial.

“Based on our comprehensive survey, which followed a feasibility study of non-dedicated sensor usage, we argue that non-dedicated sensors provide a viable alternative to future smart city applications,” Soyata said.