Sodium Could Replace Lithium in Batteries

While the lithium-ion battery has “enabled the modern world,” its ubiquity is causing environmental issues. The lithium batteries that power our electronic devices and electric vehicles have a number of drawbacks. The electrolyte — the medium that enables electrons and positive charges to move between the electrodes — is a flammable liquid. What’s more, the lithium they’re made of is a limited resource that is the focus of major geopolitical issues. Specialists in crystallography at the University of Geneva (UNIGE) have developed a non-flammable, solid electrolyte that operates at room temperature. It transports sodium — which is found everywhere on earth — instead of lithium. It’s a winning combination that also means it is possible to manufacture batteries that are more powerful. The properties of these “ideal” batteries would be based on the crystalline structure of the electrolyte, a hydroborate consisting of boron and hydrogen. The UNIGE research team has published a real toolbox in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science containing the strategy for manufacturing solid electrolytes intended for battery developers.

The challenge of storing energy is colossal for sustainability initiatives. Indeed, the development of electric vehicles that do not emit greenhouse gases hinges on the existence of powerful, safe batteries, just as the development of renewable energies — solar and wind — depends on energy storage capacities. Lithium batteries are the current answer to these challenges. Unfortunately, lithium requires liquid electrolytes, which are highly explosive in the event of a leak. “What’s more, lithium isn’t found everywhere on earth, and it creates geopolitical issues similar to those surrounding oil. Sodium is a good candidate to replace it because it has chemical and physical properties close to lithium and is found everywhere,” said Fabrizio Murgia, a post-doctoral fellow in UNIGE’s Faculty of Sciences.

Too high a temperature

The two elements — sodium and lithium — are near each other in the Periodic Table. “The problem is that sodium is heavier than its cousin lithium. That means it has difficulty making its way around in the battery electrolyte,” said Matteo Brighi, a post-doctoral fellow at UNIGE and the study’s first author. Accordingly, there is a need to develop electrolytes capable of transporting cations such as sodium. In 2013 and 2014, Japanese and American research groups identified hydroborates as good sodium conductors at over 120°C. At first glance, this is an excessive temperature for everyday use of batteries — but a godsend for the Geneva laboratory.

With decades of expertise in hydroborates used in applications such as hydrogen storage, the Geneva crystallographers set about working on lowering the conduction temperature. “We obtained very good results with excellent properties compatible with batteries. We succeeded in using hydroborates as an electrolyte from room temperature to 250°C with no safety issues. What’s more, they resist higher potential differences, meaning the batteries can store more energy,” said Radovan Cerny, a professor in UNIGE’s Laboratory of Crystallography and project leader.

The solution: a disorder

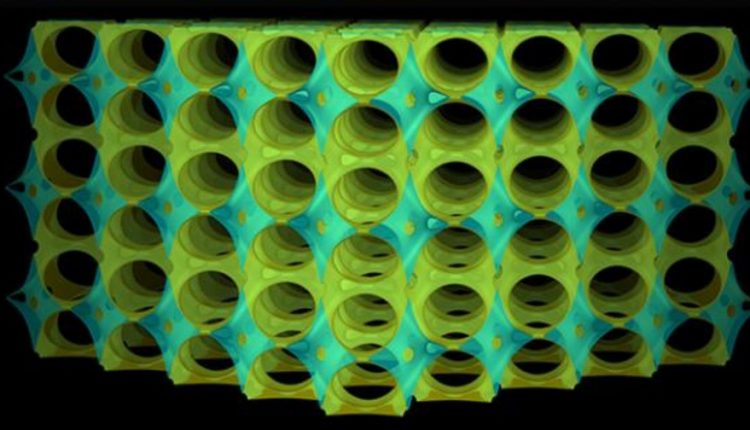

Crystallography — a science positioned between mineralogy, physics and chemistry — is used to analyze and understand the structures of chemical substances and predict their properties. Thanks to crystallography, it is possible to design materials. It is this crystallographic approach that was used to implement the manufacturing strategies published by the trio of Geneva-based researchers. “Our article offers examples of structures that can be used to create and disrupt the hydroborates,” says Murgia. The structure of the hydroborates allows spheres of boron and negatively charged hydrogen to emerge. These spherical spaces leave enough room for positively charged sodium ions to pass.”Nevertheless, as the negative and positive charges attract each other, we needed to create disorder in the structure to disrupt the hydroborates and allow the sodium to move,” continues Brighi.

Source: University of Geneva (UNIGE)