Sonar Tech Determines Safe Drinking Water

Over 30 years ago, the public was introduced to sonar tech on submarines via the film The Hunt for Red October. Now, a team of scientists at the University of Missouri is using this same sonar technology as inspiration to develop a rapid, inexpensive way to determine whether water is safe to drink.

The scientists say they can determine changes in the physical properties of liquids.

“If the water isn’t drinkable, then our method will tell you that something is wrong with the water,” said Luis Polo-Parada, an associate professor of pharmacology and physiology in the MU School of Medicine and investigator at the MU Dalton Cardiovascular Research Center. “For instance, if a facility removes salt from seawater in order for water to be safe for drinking, our method can help alert the facility to potential changes such as an issue with the desalination process.”

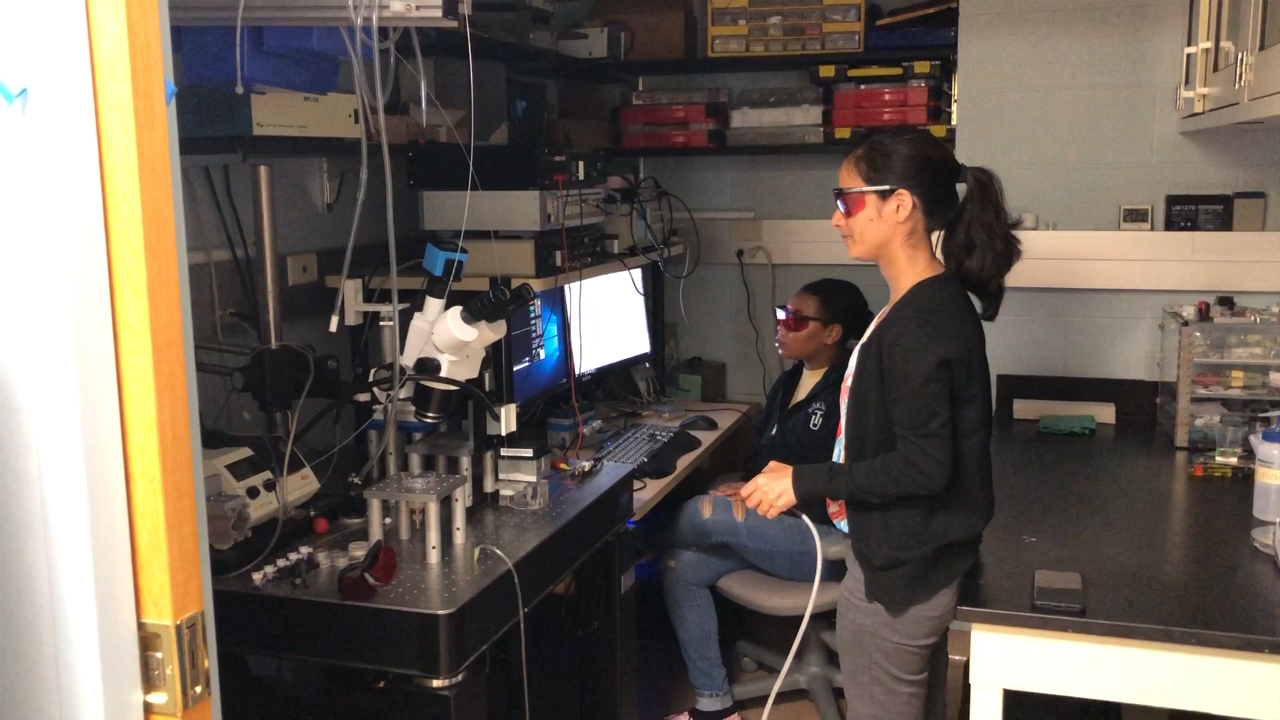

The instrument is designed to analyze the quality of liquids using the photoacoustic effect, or the generation of sound waves after the light is absorbed in a material. Drops of seawater, dairy milk or ionic liquids, a class of molten salt, were used in the study. The MU scientists believe this might be the first use of this technology to analyze such small liquid samples.

“Let’s use cymbals as an analogy,” said Gary A. Baker, associate professor of chemistry in the MU College of Arts and Science. “Sunlight causes the cymbals to heat up and create a constant ringing sound. Here, on a much smaller scale, we create the same effect by sending flashes of laser light at our tiny homemade cymbal, which is the tape, and measure the speed of the sound that is generated.”

The team is working to refine its recording methods and equipment to provide commercial industries with an inexpensive way to monitor the quality of liquids, such as the percentage of alcohol in alcoholic beverages, the amount of inferior oil in fraudulent olive oils, the quality of honey and the amount of sugar or sugar substitutes in soft drinks.

How it Works

A tattoo removal laser machine sends out a series of brief flashes of light each lasting about 10 nanoseconds. The flashes of light travel through a fiber optic cable wrapped on one end with paint-on liquid electrical tape. The cable’s end, submerged in the liquid, converts the laser light into sound. The sound is recorded by a microphone and the data is analyzed in real-time.