Spintronic RAMs Could Realize MRAM Potential

The potential of MRAM as the short-term memory that allows quick access to various computer programs has been known since the 1980s, but its development has been slow. Recently, scientists at Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech) explored a new material combination that sets the stage for magnetic random access memories, which rely on spin—an intrinsic property of electrons—and could outperform current storage devices.

The novel strategy to exploit spin-related phenomena in topological materials could spur several advances in the field of spin electronics and the Tokyo Tech researchers’ study provides additional insight into the underlying mechanism of spin-related phenomena.

Spintronics is a modern technological field where the “spin” or the angular momentum of electrons takes a primary role in the functioning of electronic devices. In fact, collective spin arrangements are the reason for the curious properties of magnetic materials, which are popularly used in modern electronics. Researchers globally have been trying to manipulate spin-related properties in certain materials, owing to a myriad of applications in devices that work on this phenomenon, especially in non-volatile memories. These magnetic non-volatile memories, called MRAM, have the potential to outperform current semiconductor memories in terms of power consumption and speed.

A team of researchers from Tokyo Tech, led by Associate Professor Pham Nam Hai, recently published a study in Journal of Applied Physics on unidirectional spin Hall magnetoresistance (USMR), a spin-related phenomenon that could be used to develop MRAM cells with an extremely simple structure. The spin Hall effect leads to the accumulation of electrons with a certain spin on the lateral sides of a material. The motivation behind this study was that the spin Hall effect, which is particularly strong in materials known as “topological insulators,” can result in a giant USMR by combining a topological insulator with a ferromagnetic semiconductor.

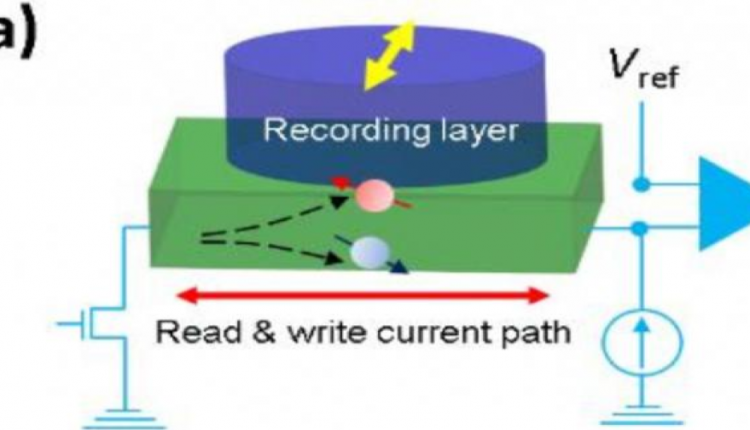

Basically, when electrons with the same spin accumulate on the interface between the two materials due to the spin Hall effect, the spins can be injected to the ferromagnetic layer and flip its magnetization, allowing for “memory write operations,” which means the data in storage devices can be “re-written.” At the same time, the resistance of the composite structure changes with the direction of the magnetization owing to the USMR effect. Because resistance can be measured using an external circuit, this allows for “memory read operations,” in which data can be read using the same current path with the write operation. In existing material combination using conventional heavy metals for the spin Hall effect, however, the changes in resistance caused by the USMR effect are extremely low—well below 1%—which hinders the development of MRAMs utilizing this effect. In addition, the mechanism of the USMR effect seems to vary according to the combination of material used, and it is not clear which mechanism can be exploited for enhancing the USMR to over 1%.

To understand how material combinations can influence the USMR effect, the researchers designed a composite structure comprising a layer of gallium manganese arsenide (GaMnAs, a ferromagnetic semiconductor) and bismuth antimonide (BiSb, a topological insulator). Interestingly, with this combination, they were successful in obtaining a giant USMR ratio of 1.1%. In particular, the results showed that utilizing phenomena called “magnon scattering” and “spin-disorder scattering” in ferromagnetic semiconductors can lead to a giant USMR ratio, making it possible to use this phenomenon in real-world applications. The study is the first to demonstrate that it is possible to obtain an USMR ratio larger than 1%, several orders of magnitude higher than those using heavy metals for USMR. The results also provide a new strategy to maximize the USMR ratio for practical device applications and could play a key role in the development of spintronics.

Conventional MRAM structure requires about 30 ultrathin layers, which is very challenging to make. By utilizing USMR for read-out operation, only two layers are needed for the memory cells. “Further material engineering may further improve the USMR ratio, which is essential for USMR-based MRAMs with an extremely simple structure and fast reading. Our demonstration of an USMR ratio over 1% is an important step toward this goal,” said Dr. Hai.

Source: Tokyo Institute of Technology