Student creates interactive Pac-Man game with microorganisms

An easily assembled smartphone microscope provides new ways of interacting with and learning about common microbes. The open-source device could be used by teachers or in other educational settings.

A new 3-D printed, easily assembled smartphone microscope developed at Stanford University turns microbiology into game time. The device allows kids to play games or make more serious observations with miniature light-seeking microbes called Euglena. Ingmar Riedel-Kruse An easily assembled smartphone microscope developed at Stanford allows people to study the light-seeking microbes called Euglena.

“Many subject areas like engineering or programming have neat toys that get kids into it, but microbiology does not have that to the same degree,” said Ingmar Riedel-Kruse, an assistant professor of bioengineering. “The initial idea for this project was to play games with living cells on your phone. And then it developed much beyond that to enable self-driven inquiry, measurement and building your own instrument.”

Riedel-Kruse named his device the LudusScope after the Latin word “Ludus,” which means “play,” “game” or “elementary school.” He and first author Honesty Kim, a graduate student in Riedel-Kruse’s lab, are set to publish details of the LudusScope in PLOS ONE on Oct. 5.

Playing with cells

The LudusScope consists of a platform for the microscope slide where the Euglena swim freely, surrounded by four LEDs. Kids can influence the swimming direction of these light-responsive microbes with a joystick that activates the LEDs.

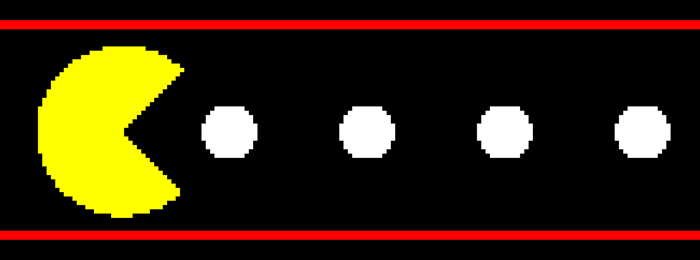

Above the platform, a smartphone holder positions the phone’s camera over a microscope eyepiece, providing a view of the cells below. Ingmar Riedel-Kruse PAC-MAN-like game with Euglena. Ingmar Riedel-Kruse Euglena soccer.

On the phone, children can run a variety of software that overlay on top of the image of the cells. One looks like the 1980s video game Pac-Man, with a maze containing small white dots. Kids can select one cell to track, then use the LED lights to control which direction the cell swims in an attempt to guide it around the maze and collect the dots. Another game looks like a soccer stadium. Kids earn points by guiding the Euglena through the goal posts.

Other non-game applications provide microscope scale-bars, real-time displays of swimming speed or zoomed-in views of individual cells. These let kids collect data on Euglena behavior, swimming speed and natural biological variability. Riedel-Kruse encourages teachers to have students model the behaviors they see using a simple programming application called Scratch, which many kids already learn in school.

Each of the elements, from the plastic microscope to the chamber that holds the Euglena, is something youngsters can build themselves from simple, easily available parts.

Complex beginnings

The project began as part of a Stanford bioengineering class Riedel-Kruse taught, with much more complex parts. But he wondered if the elements could be simplified for younger learners.

“We wondered if we could make it so easy to replicate that even middle-schoolers could build it,” he said.

In its current iteration, a teacher who wanted to use the device in class could start with the open-source 3D printing patterns and software included as part of the paper. An increasing number of schools have 3D printers, but those that don’t can send the plans to a professional printer. That produces pieces to construct the stage that holds a microscopic slide and a holder for the microscope eyepiece and smartphone.

For the joystick controller, students would need to wire a small circuit out of common electronics parts to receive signals from the joystick and transmit them to the LEDs.

Euglena are already commonly used in classrooms and they can be purchased through biological supply companies. For the game, Euglena swim within a chamber made by adhering strips of double-sided tape to the slide and to the cover slip.

The act of building, observing, interacting and modeling the cells fits easily within the new science learning guidelines emphasized by the Next Generation Science Standards being adopted by many schools, Riedel-Kruse said.

Expert opinion

The real experts on what makes for a fun game are the kids who Riedel-Kruse hopes might one day use the LudusScope. To test it out, his team took the scope to a walk-by science event and also invited students and teachers to the lab.

Science teachers and high-school students who had a chance to interact with the LudusScope saw potential for education, although Riedel-Kruse said they valued the game aspect less than other properties of the LudusScope.

“I thought the interactive cell stimulation and the resulting games was the coolest thing but the teachers and students didn’t necessarily agree,” Riedel-Kruse said. “What they were more excited about is the more basic things like the ability to build your own instrument, that multiple people can see the screen at the same time and that you can select and track individual cells.”

Riedel-Kruse is continuing to update the LudusScope with input from teachers and students. He has received a seed grant to collaborate with an educational game company to carry out more user studies and to develop a science kit. He expects that kit could be available for purchase in over a year.

Additional authors include Lukas C. Gerber, Daniel Chiu, Seung Ah Lee, Nate Cira and Sherwin Yuyang Xia. Riedel-Kruse is also a member of Stanford Bio-X. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation and a Stanford Graduate Fellowship.

More information: Stanford University

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.