Chromebooks, laptops that run an operating system based entirely around Google’s Chrome web browser, were never destined for success. They were slow, lacked storage and had a weak set of applications. Like the netbook, it was said they would find a niche as a cheap alternative to the laptop, before disappearing into the ether. And yet, somehow, they prevailed.

This year, the Chromebook became the most popular device in US education, commanding an intimidating 58 percent market share in schools – we feature one in our best laptops for students list for that reason. The recent uptick in PC sales is partly down to the Chromebook too. Notably, they outsold the Mac in the US in 2016.

But as successful as the Chromebook has become, it is yet to appeal to the content creators, the prosumers, the kind of people that put down their phones and fire up a keyboard when they want to get some work done. That’s where the Pixelbook comes in.

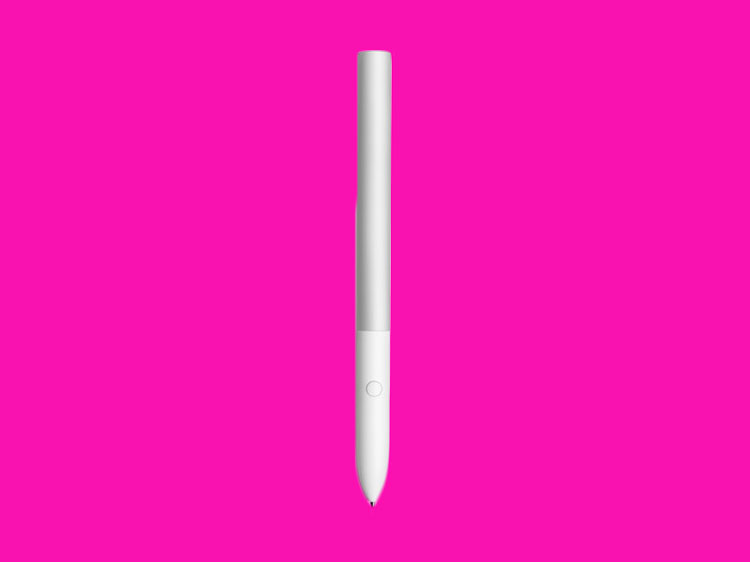

The Pixelbook is Google’s vision of what a laptop should be. It is ludicrously thin at just under 10.3mm thick and weighs 1.1kg. Its chassis and accompanying Pixelbook Pen stylus are made entirely from aluminium, while its trackpad and external stripe—the latter of which houses the antennae for WiFi and Bluetooth—are made from Gorilla Glass. It can contort into a tablet for drawing, or stand up like a tent for watching movies. The Pixelbook is a premium piece of hardware with a premium ($999 and up) price tag to match—and, like the Chromebook Pixel before it, I’m not sure anyone will buy one.

The problem certainly isn’t the hardware. The Pixelbook is as well built and as accomplished as anything that Apple or Microsoft has made. Everything about it feels expensive. The glass trackpad, which supports two and three-finger gestures, is smooth to the touch and makes scrolling effortless. ‘New touch processing algorithms’ noticeably improve palm rejection and finger tracking, while there’s a satisfying physical click too (I’m told each touchpad click is individually tuned on each Pixelbook before it leaves the factory). The keyboard, while shallow even by laptop standards with less than 1mm of travel, is full size, backlit and surprisingly comfortable to type on. Meanwhile, the glass stripe on the lid works far better aesthetically than the one on the Pixel phone

The only downside to the design is the chunky bezel around the display, which looks dated compared to the likes of the Dell XPS 13 and Apple Macbook. The Pixelbook screen doesn’t detach into a tablet either, although the utility of such a design is questionable.

“We optimised the device to make it as thin as possible,” said Google product manager Kevin Tom.

Function Over Form

“To do that we had to move some things into the bezels of the screen that we may not have had to otherwise…The Pixelbook has to work really well as a laptop. We took that as one of the starting points in the design process. When you look at convertible form factors you’re always making tradeoffs. It didn’t feel right to push that angle. The thing that was always bothering users in all our research was the size and the weight of those devices. If you have a convertible laptop, but it’s way thicker than a tablet to hold, you’re not going to use it in tablet mode.”

Internally, the Pixelbook impresses too. The $999 model comes equipped with 128GB of storage, an Intel Core i5 Y-series processor (a 7th-gen Kaby Lake version, for those interested) and 8GB of memory. $1199 buys the same model with 256GB of storage, while a whopping £1699 buys an Core i7 Y-series processor 16GB of memory and 512GB of super-fast NVMe storage (other models use slower eMMC storage, which you typically find in tablets and phones). Battery life is rated at 10 hours across the board. The high-resolution 2,400×1,600 pixel screen remains at a useful 3:2 aspect ratio—as used in the Microsoft Surface—which results in more vertical working space. There are just two USB 3.1 Type-C ports, but that’s one more than a Macbook and both can be used for charging. There’s a headphone jack, but sadly no SD card slot for photographers.

Its omission is indicative of the larger problem Google faces with the Pixelbook: just who is it for? Chrome OS has come on leaps and bounds since its introduction in 2011, including new multitasking features as well as the ability to run Android apps. You can use three finger swipes to bring up a task switcher, while Android phone apps can be dragged around the desktop inside a window. But, while Android versions of Microsoft Office, AutoCAD and Adobe Photoshop Touch will satisfy some users, they pale in comparison to the full desktop versions that run on Macbooks and Surfaces. Tweaking pictures in Photoshop and stitching together 4K videos in Adobe Premier are no longer tasks performed solely by professionals, but by budding photographers and YouTubers too.

An App Expansion

Google maintains that it’s working closely with Adobe to bring over more apps, but there’s no guarantee it will happen. That’s a shame, since there are some compelling use cases for the Pixelbook. The Pixelbook Pen, which is sold separately for $99, sports around 2000 levels of pressure sensitivity and support for tilt awareness. That’s not as high as the 4096 of Microsoft’s Surface pen, but Google has ploughed its efforts into making the pen as fast as possible.

“We worked with a bunch of app developers to make sure that they use the latest fast ink tech,” said Google product manager Alex Kuscher.

“It really feels like ink coming out of your pen, instead of the latency that you normally see where you have lag. Google Keep has it and so does note taking app Squid. We look at the entire stack in the Pixelbook. We look at the graphics stack, all the way to the applications on Android or Chrome OS to make it as fast as we can get it. We took milliseconds out of every part of the graphics stack, bypassing a bunch of things that it normally goes through. A few additional milliseconds we cut off by predicting a little bit ahead where your stroke goes.”

While I’m no artist, I find the pen responds quickly to each stroke. It’ll be interesting to see how Google’s effort stands up to the Surface Pen, which Microsoft boldly proclaimed to be ‘the fastest in the world’ earlier this year. Either way, the Pixelbook Pen has uses outside of drawing. By holding down a button on the side, you can cut out a snippet from any app and send it to Google Assistant, which happily identifies the thing, person, or place you’ve highlighted and brings up a web search or a Google Map location in response. Google Assistant on the Pixelbook works just like she (or he) does on Android and Google Home, integrating with smart home devices, calendars and email. You can even type in commands directly to the assistant instead of speaking them (although, the Pixelbook does pack five microphones for such occasions)

Synchronicity With The Pixel Phone

There other little touches that make the Pixelbook appealing too. If it loses WiFi connectivity, it can automatically use your Pixel phone’s via “instant tethering,” which does all the hotspot setup for you. Because it uses Android apps instead of desktop ones, the Pixelbook allows for offline downloads of shows, a feature previously limited to iOS, Android and some Windows 10 devices. If you live your life in Google Drive, then the ability to automatically offline-sync the last 500 uploads is a potential life-saver. Being able to run apps like Instagram, which have no desktop equivalent, is also neat. In theory, you can snap a photo on your phone (which uploads it to Google Drive), edit it in Photoshop Touch and upload it to Instagram without a needless back and forth between devices.

I’m skeptical that’s enough to lure over laptop users. The very strengths that have made Chromebooks so successful in education—where a browser-based, centrally managed computer is hugely appealing—are limitations to those that need to get work done in high-performance apps. Maybe the app ecosystem will expand, maybe it won’t. Maybe, if I come to use one daily, I’ll love it. I was wrong about the Chromebook. Maybe the Pixelbook will prove me wrong again.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.