These owls are having a hoot- but you won’t hear them

Many people see the owl as a wise old creature, and this is certainly reflected in the fact that there are many species of owls that are able to hunt in effectively silence.

The owls suppress their noise at sound frequencies above 1.6kHz well over the range that can be heard by humans so they can hunt in peace.

A team of researchers, studying the acoustics of owl flight, including Justin W. Jaworski, Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering and mechanics at Lehigh’s P.C. Rossin College of Engineering and Applied Science, are working to pinpoint the mechanisms that accomplish this virtual silence to improve man-made aerodynamic design – of wind turbines, aircraft, naval ships and, even, automobiles.

The team has succeeded through physical experiments and theoretical modeling, by using the downy canopy of owl feathers as a model to inspire the design of a 3-D printed, wing attachment that reduces wind turbine noise by a remarkable 10dB – without impacting aerodynamics.

Further investigation has taken place to see how such a design can reduce roughness and trailing-edge noise. In particular, trailing-edge noise is prevalent in low-speed applications and sets their minimum noise level. The ability to reduce wing noise has implications beyond wind turbines, as it can be applied to other aerodynamic situations such as the noise created by air seeping through automobile door and window spaces.

Findings will be published in two papers; ‘Bio-inspired trailing edge noise control’ in the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Journal, and ‘Bio-inspired canopies for the reduction of roughness noise’ in the Journal of Sound and Vibration.

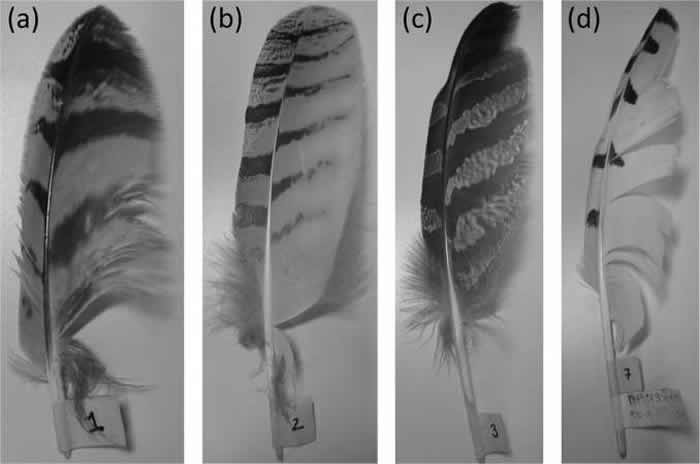

The researchers specifically looked at the velvety down that makes up the upper wing surface of many large owls – a unique physical attribute, even among birds, that contributes to owls’ noiseless flight. As seen under a microscope, the down consists of hairs that form a structure similar to that of a forest. The hairs initially rise almost perpendicular to the feather surface but then bend over in the flow direction to form a canopy with interlocking barbs at the their tops – cross-fibers.

After realizing that the use of a unidirectional canopy, with the cross-fibers removed, was the most effective, as it didn’t produce high-frequency self-noise of the fabric canopies, but still suppressed the noise-producing surface pressure – they created a 3-D-printed, plastic attachment consisting of small ‘finlets’ that can be attached to an airfoil (or, wing).

The finlet invention may be retrofitted to an existing wing design and used in conjunction with other noise-reduction strategies to achieve even greater noise suppression.

Jaworski commented: “The most effective of our designs mimics the downy fibers of an owl’s wing, but with the cross-fibers removed.”

Jaworski added: “The canopy of the owl wing surface pushes off the noisy flow. Our design mimics that but without the cross fibers, creating a unidirectional fence – essentially going one better than the owl.”

More information: Phys.org

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.