Since robots can do just about anything, why not send one into the esophagus and stomach to patch wounds or perform other actions.

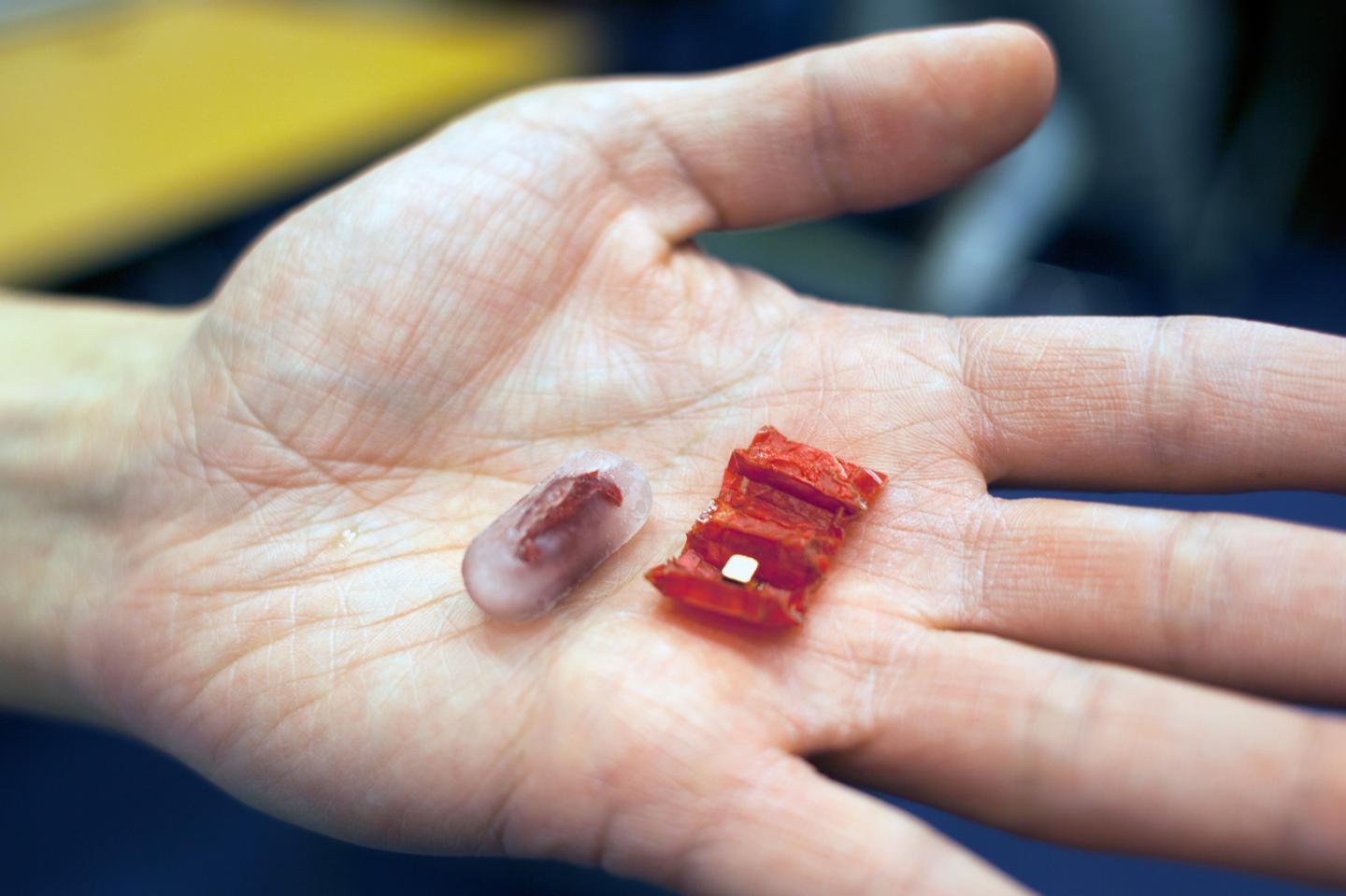

Researchers at MIT, the University of Sheffield, and the Tokyo Institute of Technology have used a simulated esophagus and stomach to demonstrate how a tiny origami robot can unfold itself from a swallowed capsule the size of a pill, and then, propelled by external magnetic fields, crawl across the stomach wall to remove a swallowed button battery or patch a wound.

“It’s really exciting to see our small origami robots doing something with potential important applications to health care,” said Daniela Rus, who also directs MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL). “For applications inside the body, we need a small, controllable, un-tethered robot system. It’s really difficult to control and place a robot inside the body if the robot is attached to a tether.”

This isn’t the first origami robot that Rus’ team has developed. Last year it presented one at a conference that looked different in appearance, but was able to navigate in the same way, using “stick-slip” motion, which works by sticking its appendages to a surface through friction when it moves, but then gets free when its body tries to change its weight distribution.

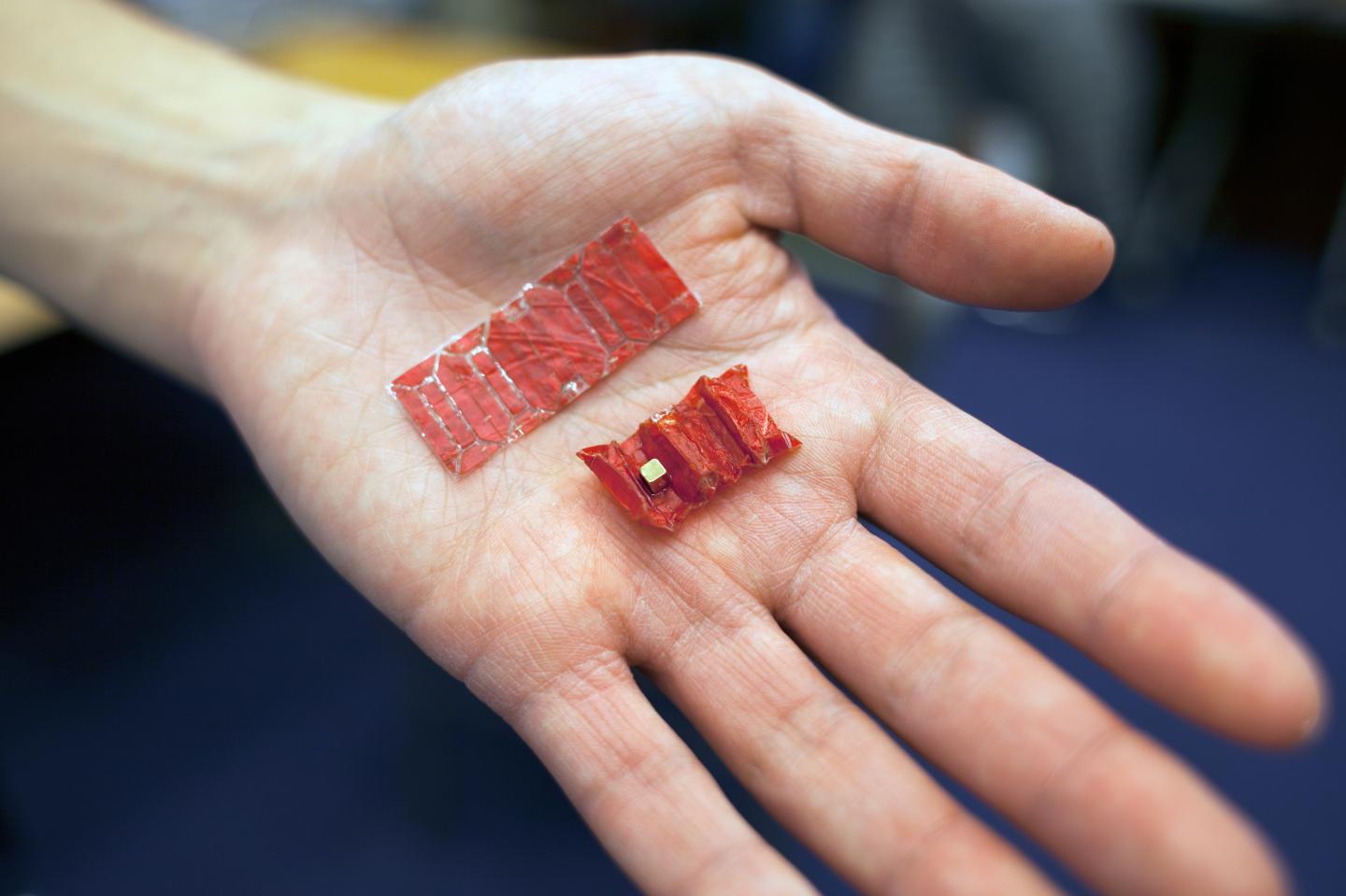

The new robot is composed of two layers of structural material that shrinks when heated and its pattern of slits on the outer layers determines how the robot will fold when the middle layer contracts.

Since the stomach is quite slippery, the robot cannot solely navigate based on “sticking” behavior, though.

“In our calculation, 20 percent of forward motion is by propelling water — thrust — and 80 percent is by stick-slip motion,” said Shuhei Miyashita, who was a postdoc at CSAIL when the work was done and is now a lecturer in electronics at the University of York. “In this regard, we actively introduced and applied the concept and characteristics of the fin to the body design, which you can see in the relatively flat design.”

To compress the tiny robot to a size small enough to fit inside of a capsule, the team came up with a rectangular robot design that included accordion folds perpendicular to its long axis and pinched corners that act as points of traction.

One of the accordion folds contains a permanent magnet that responds to changing magnetic fields outside the body to control the robot’s motion. All of the forces that are applied to the robot are rotational. So a quick rotation will cause it to spin in place, while a slower rotation will cause it to pivot around one of its fixed feet. In one the team’s’ experiments, it even had the robot use the same magnet to pick up the button battery.

According to the team, 3,500 button batteries are swallowed annually in the U.S. alone. While most of the time, the batteries are digested normally, if they come into prolonged contact with the tissue of the esophagus or stomach, they can cause an electric current that produces hydroxide, which burns the tissue. This is one of the potential applications that Miyashita was focused on the most.

“Shuhei bought a piece of ham, and he put the battery on the ham,” said Rus. “Within half an hour, the battery was fully submerged in the ham. So that made me realize that, yes, this is important. If you have a battery in your body, you really want it out as soon as possible.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.