In an attempt to protect innocent bystanders and civilians that are too often harmed in the midst of military combat, the U.S. Army has patented a new technology that allows bullets to self-destruct if it happens to go further than intended.

“The biggest advantage is reduced risk of collateral damage,” said Stephen McFarlane an employee from the U.S. Army Armament Research, Development and Engineering Center, who worked on the limited-range projectile. “In today’s urban environments others could become significantly hurt or killed, especially by a round the size of a .50 caliber, if it goes too far.”

The concept was initially geared toward .50 caliber ammunition, but the patent refers to the entire technology and could therefore be used ion other calibers as well.

How it works

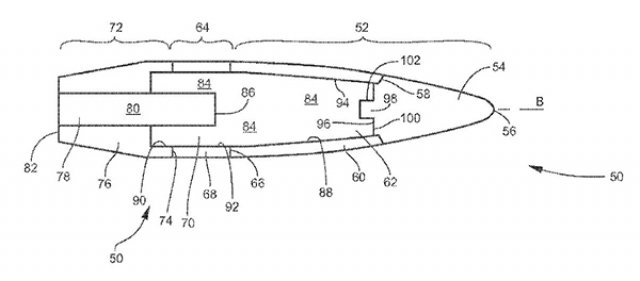

Limited-range projectiles would include pyrotechnic and reactive material. The pyrotechnic material would be ignited when the projectile is launch, which in turn ignites the reactive material. If the projectile reaches a certain range without hitting a target, the ignited reactive material instead turns the bullet into an aerodynamically unstable object, which renders it incapable of continuing its flight.

In one of the engineers’ self-destructing concepts, the projectile melts the copper jacket, which turns it into a strange shape and in another concept, the cylindrical portion of the bullet separates from the base.

To determine the distance in which the round would disassemble, only the reactive materials would need to be adjusted to keep the round from traveling and, in effect, reducing collateral damage.

The team created computerized models and simulations to compare the projectiles. A proof-of-concept test was perfected, but the results pointed to the need for minor refinements and improvements on the material mixtures used.

While the Army admits that funding for this project has currently come to a stand-still, the engineers hope that their concept will resurface.

“This was the first patent we applied for that has been approved. That in itself is an accomplishment,” said McFarlane.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.