UH Researchers Create Lens to Turn Smartphone into Microscope

Researchers at the University of Houston have created an optical lens that can be placed on an inexpensive smartphone to amplify images by a magnitude of 120, all for just 3 cents a lens.

Wei-Chuan Shih, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at UH, said the lens can work as a microscope, and the cost and ease of using it – it attaches directly to a smartphone camera lens, without the use of any additional device – make it ideal for use with younger students in the classroom.

It also could have clinical applications, allowing small or isolated clinics to share images with specialists located elsewhere, he said.

In a paper published in the Journal of Biomedical Optics, Shih and three graduate students describe how they produced the lenses and examine the image quality. Yu-Lung Sung, a doctoral candidate, served as first author; others involved in the study include Jenn Jeang, who will start graduate school at Liberty University in Virginia this fall, and Chia-Hsiung Lee, a former graduate student at UH now working in the technology industry in Taiwan.

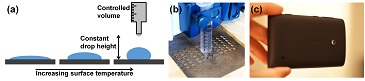

The lens is made of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), a polymer with the consistency of honey, dropped precisely on a preheated surface to cure. Lens curvature – and therefore, magnification – depends on how long and at what temperature the PDMS is heated, Sung said.

The resulting lenses are flexible, similar to a soft contact lens, although they are thicker and slightly smaller.

“Our lens can transform a smartphone camera into a microscope by simply attaching the lens without any supporting attachments or mechanism,” the researchers wrote. “The strong, yet non-permanent adhesion between PDMS and glass allows the lens to be easily detached after use. An imaging resolution of 1 (micrometer) with an optical magnification of 120X has been achieved.”

Conventional lenses are produced by mechanical polishing or injection molding of materials such as glass or plastics. Liquid lenses are available, too, but those that aren’t cured require special housing to remain stable. Other types of liquid lenses require an additional device to adhere to the smartphone.

This lens attaches directly to the phone’s camera lens and remains attached, Sung said; it is reusable.

For the study, researchers captured images of a human skin-hair follicle histological slide with both the smartphone-PDMS system and an Olympus IX-70 microscope. At a magnification of 120, the smartphone lens was comparable to the Olympus microscope at a magnification of 100, they said, and software-based digital magnification could enhance it further.

With his primary appointment in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Shih is also affiliated with the Department of Biomedical Engineering and the Department of Chemistry. His interdisciplinary team is focused on nanobiophotonics and nanofluidics, pursuing discoveries in imaging and sensing, including work to improve medical diagnostics and environmental safety. Sung said he was using PDMS to build microfluidic devices and as he worked with a lab hotplate, realized the material cured on contact with the heated surface.

Intrigued, he decided to try making a lens.

“I put it on my phone, and it turns out it works,” he said. Sung uses a Nokia Lumia 520, prompting him to say the resulting microscope came from “a $20 phone and a 1 cent lens.”

That 1 cent covers the cost of the material; he and Shih estimate that it will cost about 3 cents to manufacture the lenses in bulk. A conventional, research quality microscope, by comparison, can cost $10,000.

“A microscope is much more versatile, but of course, much more expensive,” Sung said.

His first thought on an application for the lens was educational – it would be a cheap and convenient way for younger students to do field studies or classroom work. Because the lens attaches to a smartphone, it’s easy to share images by email or text, he said. And because the lenses are so inexpensive, it wouldn’t be a disaster if a lens was lost or broken.

“Nearly everyone has a smartphone,” Sung said. “Instead of using a $30 or $50 attachment that students might use only once or twice, they could use this.”

For now, researchers are producing the lenses by hand, using a hand-built device that functions similarly to an inkjet printer. But producing the lenses in bulk will require funding, and the graduate students launched a crowdfunding campaign through Indiegogo, hoping to raise $12,000 for the equipment. They’ve raised $3,000 so far.

Undeterred, they have shared the lenses with the Ministry of Education in Taiwan and with teachHOUSTON, a math and science teacher preparation program at UH.

“I think it will be fun,” Shih said. “We could invite science teachers to watch what we do.”