Undersea Volcanic Clay Bacteria Could Change How We Search for Life on Mars

Newly discovered single-celled creatures living deep beneath the seafloor have given researchers clues about how they might find life on Mars. These bacteria were discovered living in tiny cracks inside volcanic rocks after researchers persisted over a decade of trial and error to find a new way to examine the rocks.

Researchers estimate that the rock cracks are home to a community of bacteria as dense as that of the human gut, about 10 billion bacterial cells per cubic centimeter (0.06 cubic inch). In contrast, the average density of bacteria living in mud sediment on the seafloor is estimated to be 100 cells per cubic centimeter.

“I am now almost over-expecting that I can find life on Mars. If not, it must be that life relies on some other process that Mars does not have, like plate tectonics,” said Associate Professor Yohey Suzuki from the University of Tokyo, referring to the movement of land masses around Earth most notable for causing earthquakes. Suzuki is first author of the research paper announcing the discovery, published in Communications Biology.

Magic of clay minerals

“I thought it was a dream, seeing such rich microbial life in rocks,” said Suzuki, recalling the first time he saw bacteria inside the undersea rock samples.

Undersea volcanoes spew out lava at approximately 1,200 degrees Celsius (2,200 degrees Fahrenheit), which eventually cracks as it cools down and becomes rock. The cracks are narrow, often less than 1 millimeter (0.04 inch) across. Over millions of years, those cracks fill up with clay minerals, the same clay used to make pottery. Somehow, bacteria find their way into those cracks and multiply.

“These cracks are a very friendly place for life. Clay minerals are like a magic material on Earth; if you can find clay minerals, you can almost always find microbes living in them,” explained Suzuki.

The microbes identified in the cracks are aerobic bacteria, meaning they use a process similar to how human cells make energy, relying on oxygen and organic nutrients.

“Honestly, it was a very unexpected discovery. I was very lucky, because I almost gave up,” said Suzuki.

Cruise for deep ocean samples

Suzuki and his colleagues said discovery of the bacteria was unexpected and that he almost gave up. He had helped collect the rock samples in late 2010 during the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP). IODP Expedition 329 took a team of researchers from Tahiti to Auckland. The research ship anchored above three locations along the route across the South Pacific Gyre and used a metal tube 5.7 kilometers long to reach the ocean floor. Then, a drill cut down 125 meters below the seafloor and pulled out core samples, each about 6.2 centimeters across. The first 75 meters beneath the seafloor were mud sediment and then researchers collected another 40 meters of solid rock.

Depending on the location, the rock samples were estimated to be 13.5 million, 33.5 million and 104 million years old. The collection sites were not near any hydrothermal vents or sub-seafloor water channels, so researchers are confident the bacteria arrived in the cracks independently rather than being forced in by a current. The rock core samples were also sterilized to prevent surface contamination using an artificial seawater wash and a quick burn, a process Suzuki compares to making aburi (flame-seared) sushi.

At that time, the standard way to find bacteria in rock samples was to chip away the outer layer of the rock, then grind the center of the rock into a powder and count cells out of that crushed rock.

“I was making loud noises with my hammer and chisel, breaking open rocks while everyone else was working quietly with their mud,” he recalled.

How to slice a rock

Over the years, continuing to hope that bacteria might be present but unable to find any, Suzuki decided he needed a new way to look specifically at the cracks running through the rocks. He found inspiration in the way pathologists prepare ultra thin slices of body tissue samples to diagnose disease. Suzuki decided to coat the rocks in a special epoxy to support their natural shape so that they wouldn’t crumble when he sliced off thin layers.

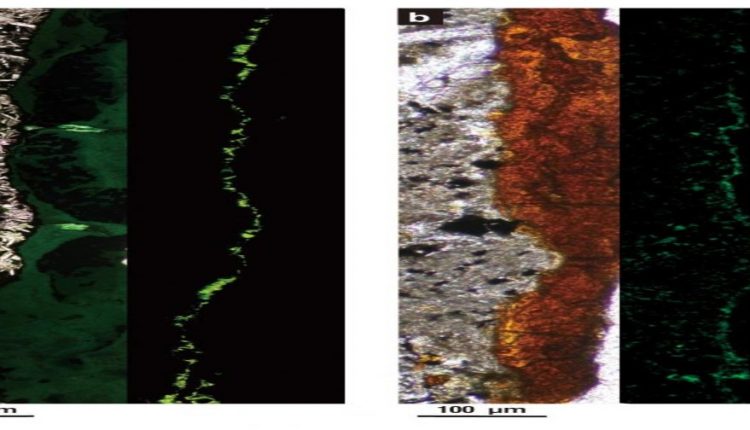

These thin sheets of solid rock were then washed with dye that stains DNA and placed under a microscope.

The bacteria appeared as glowing green spheres tightly packed into tunnels that glow orange, surrounded by black rock. That orange glow comes from clay mineral deposits, the “magic material” giving bacteria an attractive place to live.

Whole genome DNA analysis identified the different species of bacteria that lived in the cracks. Samples from different locations had similar, but not identical, species of bacteria. Rocks at different locations are different ages, which may affect what minerals have had time to accumulate and therefore what bacteria are most common in the cracks.

Suzuki and his colleagues speculate that the clay mineral-filled cracks concentrate the nutrients that the bacteria use as fuel. This might explain why the density of bacteria in the rock cracks is eight orders of magnitude greater than the density of bacteria living freely in mud sediment where seawater dilutes the nutrients.

From the ocean floor to Mars

The clay minerals filling cracks in deep ocean rocks are likely similar to the minerals that may be in rocks now on the surface of Mars.

“Minerals are like a fingerprint for what conditions were present when the clay formed. Neutral to slightly alkaline levels, low temperature, moderate salinity, iron-rich environment, basalt rock — all of these conditions are shared between the deep ocean and the surface of Mars,” said Suzuki.

Suzuki’s research team is beginning a collaboration with NASA’s Johnson Space Center to design a plan to examine rocks collected from the Martian surface by rovers. Ideas include keeping the samples locked in a titanium tube and using a CT scanner to look for life inside clay mineral-filled cracks.

Source: University of Tokyo